This Space is Getting Hot

Conditions & Atmosphere Weather: Sunny and hot, with a high near 92. Light southwest wind. Vibes: It’s a sizzler at Smuggs today, and the perfect excuse to make a splash! You should take full advantage of our pools, nearby reservoirs, and hidden swimming holes to keep cool. […]

ViewsGet your 2025/2026 Season Pass or Bash Badge – NOW!

Pass It On: Smuggs Best Deal Ends Labor Day! Winter might feel far away, but your best ski days start now. Lock in your Smuggs Season Pass or Bash Badge before 9/1/25 and score the lowest prices of the year. From unlimited access to midweek-only […]

ViewsThis Weekend is Full!

Conditions & Atmosphere Weather: A 30 percent chance of showers and thunderstorms, mainly between 2:00 pm and 5:00 pm. Partly sunny, with a high near 82. Calm Wind. Vibes: We’re excited for a Full Moon weekend that’s full of events and activities for many different interests. The weather […]

Views

Mountain Review: Mont-Sainte-Anne

MOUNTAIN SCORE #4 East Coast 61 #67 Overall WRITTEN REVIEW MOUNTAIN STATS CATEGORY BREAKDOWN See our criteria 6 Snow: 6 Resiliency: 4 Size: 6 Terrain Diversity: 6 Challenge: 7 Lifts: 7 Crowd Flow: 6 Facilities: 6 Navigation: 7 Mountain Aesthetic: GOOD TO KNOW […]

MountainMOUNTAIN SCORE

61

CATEGORY BREAKDOWN

6

Snow:

6

Resiliency:

4

Size:

6

Terrain Diversity:

6

Challenge:

7

Lifts:

7

Crowd Flow:

6

Facilities:

6

Navigation:

7

Mountain Aesthetic:

GOOD TO KNOW

1-Day Ticket: $73-$105 USD ($101-$104 CAD)

Pass Affiliation: Epic Pass (full pass only)

On-site Lodging: Yes

Après-Ski: Limited

Nearest Cities: Quebec City (1 hr), Montreal (3.5 hrs)

Recommended Ability Level:

+ Pros

-

Terrain diversity

-

Fast lifts

-

St. Lawrence River views

-

Available night skiing

-

Value

– Cons

-

Much more difficult to reach than other Northeast ski resorts

-

Some navigational challenges, especially around the summit

-

Some frontside snow reliability issues

MOUNTAIN STATS

Skiable Footprint: 547 acres

Total Footprint: 1,609 acres

Lift-Serviced Terrain: 100%

Top Elevation: 2,625 ft

Vertical Drop: 2,050 ft

Lifts: 9

Trails: 71

Beginner: 21%

Intermediate: 46%

Advanced/Expert: 33%

Mountain Review

Are you looking for a comprehensive ski resort experience in the Northeast, but don’t want the crowds of resorts further south? Well look no further than Mont-Sainte-Anne. With terrain for all abilities to enjoy, abundant and affordable lodging options, and easy access from nearby Quebec City, Mont-Sainte-Anne is a standout for visitors of all abilities and inclinations. So how does it compare to other resorts in the region?

Size and Terrain Layout

With 547 acres of skiable terrain, Mont-Sainte-Anne ranks among the largest ski areas in Quebec—and holds its own against some of the biggest resorts on the East Coast. 360-degree skiing and riding is available off the summit across half a dozen distinct terrain pods, giving the mountain a true big-mountain feel. Terrain is generally divided by ability zone, allowing lower-ability skiers and riders to enjoy much of the mountain without frequent interference from faster-moving experts; that said, a few shared junction points do exist.

360 degree skiing off of Mont-Sainte-Anne’s summit adds to the resort’s big-mountain feel.

Beginner Terrain

Mont-Sainte-Anne offers a diverse and enjoyable beginner experience. Beginner terrain is spread across multiple areas of the resort, though most first-timers will find themselves descending east off the summit toward the north side base. These green trails feature long, gently-rolling pitches with a pleasant sense of isolation, offering serene views of the largely undeveloped woodlands to the northeast. Thanks to their higher elevation and northern exposure, these zones typically maintain snow quality far better than the base-area beginner zones found at many other resorts.

One of the resort’s most unique features for adventurous beginners—particularly children—is the Forêt Enchantée (Enchanted Forest), a beginner glade located in the backside zone. This area features interactive elements, including toys and wind chimes, creating a whimsical atmosphere rarely found at other resorts. The glade area itself is widely spaced and in some sections groomed, offering a choose-your-own-adventure experience that’s accessible to a broad range of ability levels.

Once visitors are ready to return to the front side, the long but scenic La Familiale trail provides a wide, straightforward route back to the main base without requiring a lift download. For true first-timers, Mont-Sainte-Anne also offers a magic carpet learning area near the base, set apart from the main skier traffic to ensure a safer environment for learning.

TRAIL MAP

Intermediate Terrain

From the first glance at the trail map, it’s clear that Mont-Sainte-Anne is heavily catered toward intermediate skiers and riders. Aside from the expert-focused Panorama Express bowl, every terrain pod at the resort offers a wide range of blue trails, covering nearly every style of intermediate skiing. For those seeking fast, lower-angle groomers with wide cuts, the north-facing backside trails are the best option. This zone also features two excellent blue-rated glade trails with sustained vertical drops and some of the best snow preservation on the mountain.

Intermediates looking to progress from the north side will find the frontside blue trails particularly appealing, with these runs offering steeper pitches than those on the north side and often incorporating ungroomed sections that would earn a black diamond rating at many other resorts. And on busier days when the Corde Raide T-bar is running, Mont-Sainte-Anne’s often-overlooked west side offers a handful of isolated blue trails that sit well away from the masses.

Advanced Terrain

While Mont-Sainte-Anne offers fewer single-black diamond trails compared to its broad selection of blues, there’s still plenty for advanced skiers and riders to enjoy across every terrain zone. Each major pod at the resort features at least one advanced-level trail, and none feel like an afterthought. On the backside, the Mélanie Turgeon trail offers a long, rolling groomed pitch that’s perfect for those looking to pick up speed.

Mont-Sainte-Anne caters most heavily towards intermediate skiers, but there are plenty of options to keep beginner and advanced skiers occupied.

On the front side, advanced visitors will find the Panorama Express pod particularly appealing, with a variety of steep groomers, bump runs, and glades. However, caution is warranted in this zone—many trails carry a legitimate double black diamond rating, and even some single blacks can become treacherous in adverse conditions. Thanks to the sustained pitch throughout this pod, skiers can expect a serious leg-burner on the way down, provided they’re fit enough for the challenge.

Beyond the Panorama Express area, many of the frontside blue trails also feature steep, frequently ungroomed sections, offering additional opportunities for advanced skiers looking to mix things up.

Expert Terrain

While Mont-Sainte-Anne may not offer the most extreme terrain on the East Coast, its expert offerings are far from lacking. Nearly all of the resort’s double black diamond trails are concentrated off the Panorama Express, a steep, expansive bowl that serves as an expert’s playground. With a sustained pitch and natural separation from the rest of the mountain, this zone often stays uncrowded on most days.

Skiers and riders who enjoy the tight, technical glades the East Coast is famous for will find no shortage of terrain to explore here, with roughly 100 acres of steep woods feeding directly back to the Panorama Express. Trails like Le Canyon, La Rousseau, and La Saint-Laurent deliver the classic, narrow, and challenging New England double black experience experts seek out. For those looking for a true test, La Super S offers a precipitously steep, often icy groomed pitch that demands precision—and is really best reserved for those with sharp edges and strong nerves.

Mont-Sainte-Anne isn’t the most freestyle-oriented mountain out there, though it does feature one major terrain park with a range of features.

Terrain Parks

Mont-Sainte-Anne’s primary terrain park is located on the Grande-Allée trail, descending east from the summit. While it’s the resort’s only major park, it’s well-built, easily accessible via the gondola, and lappable from the (admittedly slow) La Tortue lift. The park typically features a range of small to medium-sized features, making it approachable for a variety of ability levels, though it’s not quite up to the caliber of the largest parks elsewhere in the East. Its high-elevation location helps preserve snow quality, though its eastern aspect can occasionally expose it to sun and variable conditions. Additionally, a beginner park is often set up near the base area, offering an accessible option for newer park riders.

Snow and Resiliency

Mont-Sainte-Anne averages 169 inches of snowfall annually—a healthy total that’s competitive with many East Coast destinations, though slightly behind some resorts in northern Vermont. The resort’s far northern latitude helps it avoid many of the midwinter warm spells that impact stateside resorts; however, the south-facing frontside terrain can still see variable conditions even during the core season. Thanks to relatively modest crowds compared to U.S. resorts, snow preservation often outperforms expectations, particularly in the resort’s large network of gladed terrain.

The vast majority of trails are supported by snowmaking infrastructure, and when combined with the mountain’s colder climate than parts of the U.S., key trails typically remain well-covered throughout the heart of winter. That said, Mont-Sainte-Anne is not immune to the East Coast’s trademark thaw cycles, which can cause melt-outs—with the south-facing front side, which includes all of the true expert terrain, being the most susceptible. That said, even during low-snow periods, the more sheltered northern face tends to hold snow quite well.

Most of Mont-Sainte-Anne’s skiable footprint is served by a fleet of high-speed lifts, although they are generally on the older side.

Lifts

Mont-Sainte-Anne’s lift setup is generally a strong suit, although some lifts are starting to show their age. All major terrain zones at Mont-Sainte-Anne are served by a fleet of modern high-speed lifts and a gondola, with the exception of the west side trails. For most visitors, lift placement is intuitive, allowing for quick laps within each terrain pod and maintaining a loose separation between different ability levels. However, skiers looking to lap the primary terrain park on Grande Allée may find the main lift serving this zone—La Tortue—to be notably slow, with the only alternative being a long runout back to the gondola at the base.

Crowd Flow

Like most Quebec resorts, Mont-Sainte-Anne rarely experiences the large crowds typical of major U.S. destination resorts, although the busiest holidays and weekends can bring some lines at popular lifts—particularly the gondola. When it comes to crowds on the ski trails, a few choke points do exist near the frontside base, where skier traffic tends to merge onto the La Familiale and Le Court Vallon runs. That said, for most visitors, especially those skiing midweek, long lift lines and trail congestion are not much of a concern.

RECOMMENDED SKIS FOR MONT-SAINTE-ANNE

NOTE: We may receive a small affiliate commission if you click on the below links. All products listed below are unisex.

Recommended intermediate ski

Recommended advanced ski

Recommended glade ski

Recommended powder ski

On-Mountain Facilities

Mont-Sainte-Anne offers a handful of well-placed, well-maintained facilities spread across the mountain. Base lodges exist at both the main southern base and the more isolated northern base, and an on-mountain lodge sits just below the summit at the top of the La Tortue lift. Each lodge provides food and restroom access, ensuring visitors are never more than a lift ride away from a place to rest or grab a bite, regardless of which terrain zone they’re lapping. Food quality is about average for a Quebec resort—generally a step above what’s typical stateside, though not a standout—although thanks to favorable exchange rates, prices tend to come in slightly cheaper than at comparable resorts in the United States.

Navigation

When it comes to getting around Mont-Sainte-Anne, the resort features abundant, well-placed signage across the mountain. However, the resort’s highly three-dimensional footprint—particularly around the crowded summit area with its frequent double fall lines—can sometimes make navigation challenging. Guests aiming to access the north or west sides from the summit should study the trail map carefully and follow signage closely, as it’s surprisingly easy to accidentally drop into the expert-only Panorama zone.

Visitors at Mont-Sainte-Anne are never more than a lift ride away from one of the resort’s three lodges.

Mountain Aesthetic

While the area around Mont-Sainte-Anne’s southern base feels somewhat developed and commercialized, most other terrain zones—particularly on the north side—offer a more isolated, even remote atmosphere. The Enchanted Forest trail, complete with hidden wind chimes strung through the trees, creates a distinctive skiing experience unlike nearly anything else out East. And on clear days, east-facing trails also offer stunning views of the legendary Saint Lawrence River just a few miles away.

Night Skiing

It’s also worth noting that Mont-Sainte-Anne offers one of the most extensive night skiing experiences in the East, featuring 19 illuminated trails and the highest vertical drop for night skiing in Canada at 625 meters (2,050 feet). Night skiing typically operates from 4pm to 9pm on Thursdays through Saturdays during the regular season, with expanded schedules during peak periods such as the Christmas holidays and March spring break. The resort’s night footprint only extends to its beginner and intermediate trails, but it’s still quite a bit more competitive than similarly-sized resorts elsewhere in Quebec, Vermont, and Maine, which typically offer no night skiing at all.

East-facing trails at Mont-Sainte-Anne feature stunning views of the Saint Lawrence River.

Getting There and Parking

With its far northern location, Mont-Sainte-Anne is north of every other East Coast destination resort, save for nearby Le Massif de Charlevoix. Because of this, the resort can be a challenging drive for visitors coming from major U.S. metropolitan areas, and even for those in Montreal. However, the mountain is easily accessible from Quebec City, sitting just a 45-minute drive up a major highway from there. For those flying in, it’s possible to get from Quebec City’s airport to the resort base in under an hour. Once on-site, visitors will find a massive, free parking lot that easily accommodates typical skier traffic.

RECOMMENDED SNOWBOARDS FOR MONT-SAINTE-ANNE

NOTE: We may receive a small affiliate commission if you click on the below links. All products listed below are unisex.

Recommended intermediate board

Recommended advanced board

Recommended expert board

Recommended powder board

Lodging and Après-Ski

Mont-Sainte-Anne features a small but modern ski village at its base, with plenty of lodging options right on the mountain. Village accommodations lean upscale, though even the more luxurious options tend to be noticeably more affordable than comparable experiences stateside. Visitors on a tighter budget will find more affordable options just down the road in the town of Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, where a range of motels, hotels, and condos cater to all types of travelers—along with a solid selection of cafes and restaurants. For those accustomed to the steep prices near major Rocky Mountain resorts, the often sub-triple-digit lodging costs in Sainte-Anne can be reason enough to consider a trip to the region.

For après-ski, a base area bar and a handful of family-oriented dining options are available in the village. Additional food and activity choices can be found a short drive away in Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré. However, those seeking true nightlife will want to drive 40 minutes back into Quebec City proper.

Mont-Sainte-Anne’s village is small but modern, though accommodations are generally quite affordable compared to many resorts out west.

Verdict

While its exceptionally northern location will dissuade many from visiting, Mont-Sainte-Anne’s broad diversity and high-quality terrain make it a standout option versus other East Coast ski resorts. It offers some of the best value for money in the region and qualifies as a true destination resort by most metrics. Beginners and intermediates will find Mont-Sainte-Anne to be a top-tier Eastern mountain, while advanced and expert skiers should have little trouble staying engaged for multiple days on the mountain.

Pricing

For the 2024-2025 season, adult day tickets at Mont-Sainte-Anne are priced at $135 CAD, with advance purchase and shoulder-season rates dropping as low as $101 CAD—an excellent value for visitors coming from the United States. Budget-conscious skiers can also take advantage of steeply discounted half-day and night skiing options, with adult night tickets regularly available for as low as $43 CAD. For a destination resort, it’s one of the best single-day values in North America. Full Epic Pass holders also receive up to seven days of access at Mont-Sainte-Anne, although these days are shared across Stoneham, Kicking Horse, Fernie, and Kimberley.

Was the 2024–25 Season a Turning Point for North American Skiing?

This winter in the ski industry felt unlike anything we’ve seen in years—and there’s good reason for that. From operational controversies, to on-mountain accidents, to weather instability, the 2024-25 season was packed with drama, danger, and a few unexpected developments. So what do we […]

Mountain

This winter in the ski industry felt unlike anything we’ve seen in years—and there’s good reason for that. From operational controversies, to on-mountain accidents, to weather instability, the 2024-25 season was packed with drama, danger, and a few unexpected developments.

So what do we make of all this, and what do these developments mean for the future of the ski industry? In this piece, we’ll dive deep into the most notable things that happened across the North American ski world this winter—and why they matter as you plan next year’s ski trips. Let’s jump right into it.

Striking ski patrollers at Park City, UT this past December. The labor dispute reached a resolution after 12 days following a busy holiday period.

Part 1: Labor Unrest

Let’s start with what may have been the most disruptive storyline of the year: ski industry workers pushing back against corporate power. At Park City Mountain in Utah, the ski patrol union made headlines by launching a full-scale strike over contract negotiations. The patrollers, who are employed by Vail Resorts, had been pushing for higher wages, better working conditions, and stronger safety measures. After months of stalled negotiations, they walked off the job on December 27, creating a huge headache for the resort just as peak season was getting underway.

Vail Resorts then responded by flying in patrollers from other resorts they owned around the country, hoping to effectively replace the team on strike; however, the resort still found itself unable to get huge swaths of terrain open, with the overcrowded areas that did actually open facing unconscionable lift lines. This was the first ski patrol strike of its kind in more than 50 years, and it reignited national conversations about labor conditions in the ski industry. The strike reached a resolution after 12 days, but not until the patrollers had walked off the scene for the vast majority of the December holiday period, upending thousands of people’s vacations. Vail Resorts is now facing a class-action lawsuit from some of these visitors, who claim the company intentionally failed to warn them about the strike and its potential impacts.

Park City wasn’t the only Vail-owned resort where worker concerns boiled over. In the wake of what happened with the ski patrol there, patrol unions at Keystone and Crested Butte also voiced public frustrations—though both mountains eventually reached agreements with Vail Resorts. Notably, Keystone ski patrollers had only voted to unionize for the first time in spring 2024, making this the first time a bargaining agreement was ever negotiated with Vail.

Several new ski resorts, including Arapahoe Basin (pictured) voted to unionize within the past year.

That being said, it’s worth noting that this year’s unionization developments were not exclusive to Vail-owned mountains. Solitude and Arapahoe Basin, both of which are now owned by Alterra, voted to unionize within the past year, although neither has at least publicly reached a contract. Other resorts out west such as Whitefish and Eldora have taken similar steps as well. Patrollers from these mountains raised similar concerns to that of Park City’s patrollers, citing stagnant wages and lack of career progression in the move to unionize.

Besides the ski patrol strike, the highest-profile labor-related event arguably took place at Breckenridge, another Vail-owned mountain. Employees took to social media to expose unsafe and substandard conditions in company-provided housing. Reports described units without functioning heat during sub-zero cold snaps, no hot water for extended periods, and pipe bursts in at least three buildings. Some employees said their apartments were effectively unlivable—a disturbing reality in one of the country’s most visited ski towns. Winter sports goers and industry observers criticized the company for prioritizing profit over the well-being of its workers, especially in light of the ski patrol strike only weeks earlier. Both of these issues became flashpoints in the larger debate about the future of labor in the ski world, where the tension between corporate growth and worker welfare is more visible than ever.

A chair on Heavenly’s Comet Express lift slid backward into another chair following a grip failure on December 23, 2024, sending five people to the hospital. Source: xamfed | Reddit

Part 2: Ski Lift Accidents

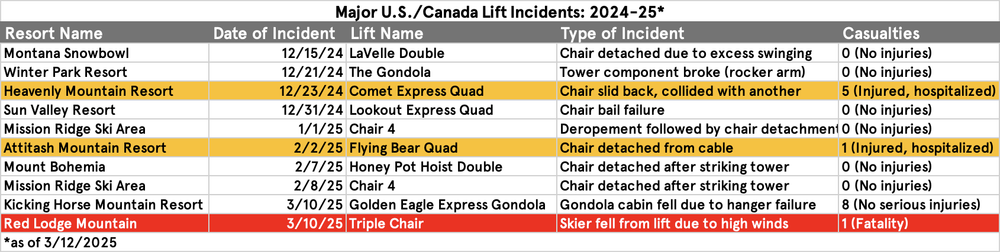

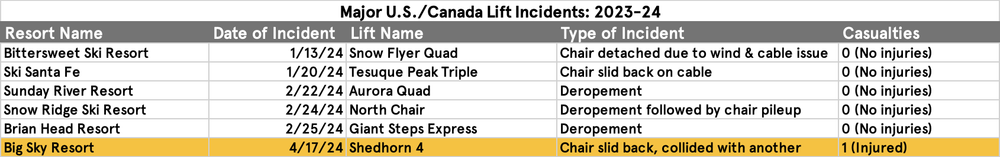

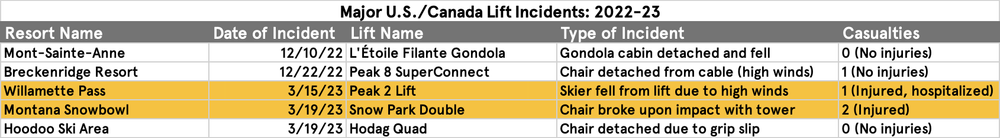

Unfortunately, it wasn’t just labor issues that rocked the industry. This season also saw a disturbing number of lift-related incidents, sparking new concerns about safety and deferred maintenance. While chairlift malfunctions are rare, there were several high-profile failures that raised eyebrows.

At least four serious incidents caused casualties this winter. At first, the focus was on Vail Resorts, with the first two out of these four accidents occurring at the resorts they owned. At Heavenly, a chair on the Comet Express slipped backwards and collided with another, causing five guests to fall nearly 30 feet and leading to multiple hospitalizations. In New Hampshire, a chair on Attitash’s Flying Bear lift detached and fell to the ground, injuring a skier who was riding the lift and prompting a state investigation. The lift was permitted to re-open more than a month later, but only after several chairs that had been found to have faulty grips were removed from the line.

On February 10, 2025, a gondola cabin detached from the cable at Kicking Horse after a hanger arm failure. Source: Brandon Shaw

But by March, it became clear that these issues were not exclusive to Vail-owned mountains. At British Columbia’s Kicking Horse, a gondola cabin on the Golden Eagle Express separated from its cable shortly after loading, forcing a dramatic rope and helicopter evacuation. And in one of the most tragic incidents of the season, a strong wind gust at Red Lodge Mountain in Montana caused the Triple Chair to derope, ejecting a rider who later died from his injuries. Looked at together, these incidents marked a dramatic increase in serious lift incidents versus previous years.

While it’s important to note that lift riding remains incredibly safe overall, several concerns have rightly been raised about whether resorts have been focusing too much on cost cutting—to the point of deprioritizing safety investments—in a time of operational strain and climate uncertainty. Notably, every resort that had a serious accident was either in a region that had a below-average season the winter prior to this one, or was owned by a company that was heavily exposed in a region with a below-average season.

Ski resorts such as Mammoth (pictured) saw snow patterns that caused significant snowpack instability in February and March this year.

Part 3: Volatile, High-Avalanche-Risk Weather Patterns

Speaking of climate uncertainty, this middle of this winter also brought one of the most alarming avalanche cycles in recent memory. The situation began with a historically low snowpack across much of North America through December and early January. Many resorts, especially in the Rockies and Sierra Nevada, were struggling with bare terrain and unseasonably warm temperatures. Then, seemingly all at once, the storms arrived—and they arrived hard, affecting some of the most prominent ski resorts on the continent.

One of the most tragic incidents occurred at Mammoth Mountain, California. On February 14, two ski patrollers were caught in an avalanche during routine mitigation work. While the area was closed to the public at the time, one of the patrollers, Claire Murphy, suffered critical injuries and later passed away on February 22. Within the two-week period of that tragic incident, in-bounds avalanches also occurred at Snowbird, Big Sky, and Palisades Tahoe, underscoring just how unstable the snowpack was across a large portion of the Western United States.

Another volatile snow cycle resulted in avalanches at Mammoth and Palisades Tahoe again in late March, with the Palisades Tahoe incident causing injuries to a ski patroller on duty. While in-bounds avalanches are still exceedingly rare, the array of high-profile incidents this winter was a sobering reminder that even in-bounds terrain can carry serious risk, especially if a massive storm system follows a long period of no new snow.

Several Southwestern ski resorts, including Lee Canyon (pictured), had decidedly difficult starts to the 2024-25 ski season.

Part 4: Southwest Drought Conditions (Until March)

While many resorts were battling too much snow, others were struggling with the exact opposite problem. Across the Southwest—from New Mexico to Southern California—ski areas experienced one of their most challenging seasons in recent memory. In New Mexico, Taos Ski Valley reported less than 100 inches of snowfall—significantly below its seasonal average of around 200 inches—resulting in the worst season since 2018. Despite a few late-season storms, the resort relied heavily on snowmaking and faced inconsistent conditions throughout the winter. Several resorts near Los Angeles faced similar issues as well, missing out on storm cycles that hit resorts further north in California.

Arizona Snowbowl in Flagstaff had an especially slow start to the season, recording just 2 inches by early January. Thankfully, a series of March storms brought the resort over 100 inches of snow by season’s end—and allowed the resort to extend its season well into the spring. However, many visitors during the core season—including some on our team—were greeted with white-ribbon snow conditions and only a small handful of trails open.

For many resorts in the Southwest, 2024-25 was a reminder of just how precarious skiing can be in marginal climates. Warm spells, inconsistent storms, and climate variability continue to threaten operations in areas that can’t rely on deep base depths or consistently cold temperatures.

Southwest Colorado’s Purgatory ski resort implemented a wave of budget cuts that culminated in a high-profile ski lift accident on March 9.

The terrible season had impacts on operations as well. Southwest Colorado’s Purgatory resort, which is owned by Mountain Capital Partners, a ski resort company that is heavily leveraged in the Southwest, faced high-profile financial issues this March. The company abruptly implemented a wave of budget cuts across its portfolio, including staff layoffs, curtailed lift operations, and scaled-back events. However, despite these issues popping up this year, Purgatory announced a new lift and small terrain expansion for the coming season, so it’s hard to place how the financial situation is really impacting MCP as a whole.

But regardless of Purgatory’s true financial state, the timing couldn’t have been worse. Just days after the staffing cuts were publicized, a 7-year-old boy fell from the Purgatory Express lift—and was later airlifted to Denver for treatment. The incident came at a moment when issues like overworked and undertrained staff, high-profile weather volatility, and lift safety were already top of mind. In many ways, it became a flashpoint that symbolized the perfect storm of challenges plaguing the ski industry this year—where financial stress, operational downsizing, and mounting incident numbers collided on the mountain.

One of Powder Mountain’s new homeowner-only checkpoints, which the resort has staffed with a team of “homeowner patrollers” to make sure that the public can’t sneak in.

Part 5: Private Club Business Models

Have the more variable winters been convincing certain ski industry stakeholders to switch up their business models? Quite possibly. Another significant trend this season has been the shift of some independently-owned ski resorts toward a private club model, aiming to offer exclusive experiences to a wealthier clientele. Utah’s Powder Mountain, under the new ownership of Netflix co-founder Reed Hastings, announced a transition to a semi-private model starting in the 2024-25 season. This approach blends public access with private skiing areas tied to real estate ownership, with about a third of the resort’s previous lift-accessed terrain now reserved exclusively for homeowners and their guests. While the move has been paired with some significant public investments, it has sparked heated backlash from longtime skiers and riders, with critics calling it a betrayal of the resort’s community-focused roots and emblematic of a broader trend where skiing is becoming less accessible to the average person.

New York’s Windham Mountain Club remains open to the public, but it has introduced a private membership with a $200,000+ initiation fee—and the resort is leaving the Ikon Pass after the 2024-25 season.

Similarly, New York’s Windham Mountain Club has been repositioning itself as a high-end destination by limiting ticket and pass sales, raising prices, and investing in upscale amenities. The resort also introduced a private membership with an initiation fee of over $200,000, which gives access to an on-site spa, a snowcat that goes up to the mid-mountain restaurant, and other perks that are designed to cater to the exclusive few who buy in. While it hasn’t closed any of its terrain to willing ticket buyers, Windham has announced it will leave the Ikon Pass after the 2024-25 season—becoming the first resort in the pass’s history to exit the partnership. This move follows several questions on whether the Ikon Pass has reached a tipping point, especially as crowding, blackout dates, and resort commoditization become more visible issues. Windham’s decision signals a growing interest among some resorts in reclaiming control over the guest experience, even if it means losing out on volume-driven passholder revenue. We’ll be keeping an eye out over the next few years to see if any other resorts drop off Ikon and its main competitor, Epic, and it remains to be seen whether Windham’s strategy is an anomaly or the canary in a coal mine.

California’s Homewood ski resort tried moving to a semi-private model, but pushback and dropped financial support resulted in the mountain having to fully suspend operations for the 2024-25 ski season.

It’s also worth briefly touching on another mountain that tried moving to a semi-private model but ended up not opening up at all: Homewood. This Lake Tahoe-adjacent resort tried installing a new gondola this past summer and floated plans to go private back in 2022, but the resort ended up having to abandon both plans—as well as their ability to open up at all—after an unnamed financial partner pulled their support. According to the resort, the investor’s withdrawal was tied to concerns over permitting timelines—delays that were ironically compounded by public backlash and speculation surrounding Homewood’s potential privatization. As of spring 2025, the resort now plans to reopen next season and remain public for the foreseeable future. But for now, it appears the long-promised gondola still won’t be making its way up the mountain.

Vermont’s Killington and Pico became two of the first ski resorts in years to shift from corporate ownership back to independent hands.

Part 6: A Return of Local Stewardship?

Despite the developments at Powder Mountain and Windham, not every shift in the independent ownership space has been about exclusivity. For the first time in years, we’re seeing one of the major ski corporations—Powdr Corp—start to back away from ski resort ownership. The ski resort mega corporation, which owned eight notable ski resorts across North America through 2024, made plans to sell five of them, including Killington, Pico, Eldora, Silver Star, and Mount Bachelor. At the end of last year, Powdr went through with the sale of Killington and Pico, although it’s worth noting that they have since gone back on their move to sell Mount Bachelor. The change marks the first time in years that a large ski conglomerate has actively offloaded ski resort assets—making for a change versus the relentless acquisition trend we’ve seen since the early 2010s.

Whether Powdr’s move is an isolated shift or the beginning of a larger trend remains to be seen. But it opens the door to a new era where corporate consolidation isn’t the only path forward—and where independent ownership doesn’t have to mean exclusivity.

After years in federal receivership, Vermont’s Burke Mountain has a new, locally-based owner.

When it comes to resorts historically owned by smaller entities, we’re also seeing them stay in local hands. A similar story unfolded this year at Burke Mountain, also in Vermont, where ownership was transferred to a local group following years of instability tied to the EB-5 investment scandal. The new ownership model emphasizes local stewardship, skier access, and long-term sustainability over short-term profit. Together, these moves challenge the narrative that independent ownership always means privatization.

Another heartening example comes from New Hampshire’s Black Mountain, where a push to become a skier-owned cooperative—similar to the Mad River Glen model—has captured attention for all the right reasons. Faced with financial uncertainty, the resort launched a grassroots campaign this winter to preserve public access and community ownership—and ended up being temporarily purchased by the company that owns and issues the Indy Pass, with the goal of transitioning the resort to a co-op model by the upcoming 2025-26 season. The managing director of the Indy Pass, Erik Mogensen, stepped in as the GM of the resort through the end of this season. The results were promising: Mogensen personally paid parking tickets for visiting skiers, staff handed out free cookies in the lift lines, and the mountain committed to staying open deep into the spring—targeting a season end date of May 3—while nearby Wildcat, owned by Vail Resorts, is closing weeks earlier than usual despite being known for its strong East Coast spring skiing. The effort didn’t just win hearts; it tripled Black Mountain’s revenue compared to the previous season. It’s a compelling counterpoint to the trend of privatization—showing how creativity, transparency, and a commitment to community can reinvigorate a small ski area without sacrificing public access.

This past winter, Deer Valley installed three new lifts and added over 300 acres of new terrain as part of the first phase of its astronomical Expanded Excellence terrain expansion.

Part 7: Continued Capital Expenditures

But even when it came to the mega-resorts, the developments in the North American ski world this winter weren’t all chaotic. As in previous years, dozens of ski resorts continued to spearhead major capital investments. While some major corporations such as Vail Resorts notably pulled back on these projects versus previous years, other high-profile resorts, including Big Sky, Jackson Hole, Banff Sunshine, and Lake Louise, installed new lifts that fundamentally improved the resort experience. And at Sun Peaks, Powder Mountain, and Deer Valley, guests found themselves able to take advantage of substantial lift-served terrain expansions, with Deer Valley’s investment adding multiple lifts and dozens of new trails—and only being the first stage in a massive 3,700-acre expansion over the next few years.

But high-profile investments weren’t the only ones that made an impact—dozens of resorts funneled money into snowmaking systems, upgraded grooming fleets, new employee housing, glade and trail work, and RFID gate infrastructure—investments that may not always grab attention, but collectively made operations smoother and skier experiences more seamless.

It wasn’t just high-profile lift and terrain expansions—ski resorts continued to invest in behind-the-scenes projects such as snowmaking and grooming.

Final Thoughts

Taken as a whole, the 2024-2025 ski season was one of extremes. It featured some of the most significant labor actions in decades, real concerns about safety and infrastructure, a sobering period of avalanche activity, dramatic regional climate impacts, and continued questions about accessibility in the evolving ski economy. But it also showed signs of resilience—and even a few encouraging shifts toward a more balanced and community-focused industry.

As we head into the off-season, one thing is clear: the ski world is changing fast. And whether you’re a casual winter sports-goer, a regular passholder, or someone who just loves watching this industry unfold, it’s worth keeping a close eye on where things are headed next.

Deer Valley Expanded Excellence Phase 1: A Surprisingly Strong Start (With One Big Catch)

Phase 1 of Deer Valley’s Expanded Excellence brings 19 new trails across 316 skiable acres, with several overlooking the massive Jordanelle Reservoir. This year, Utah’s Deer Valley opened the first phase of one of the biggest multi-year ski resort expansion projects in recent […]

Mountain

Phase 1 of Deer Valley’s Expanded Excellence brings 19 new trails across 316 skiable acres, with several overlooking the massive Jordanelle Reservoir.

This year, Utah’s Deer Valley opened the first phase of one of the biggest multi-year ski resort expansion projects in recent memory.

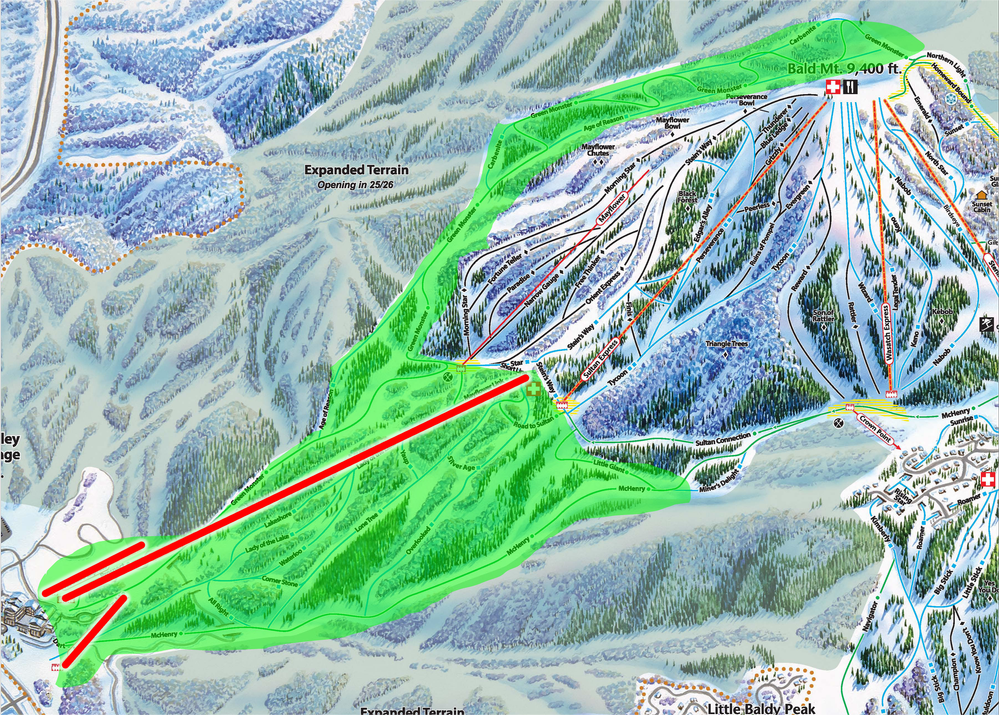

The ski-only resort, which is one of just three left in North America to prohibit snowboarding, added three new lifts for this season. The new lifts include the Keetley Express high speed six-pack, the Hoodoo Express high-speed quad, and the Aurora fixed grip quad. All of these lifts reside at or near the new Deer Valley East base area, which is south of the current Jordanelle base on US-40. This base area will eventually offer an entire base village and the country’s largest “ski beach”, but for this year, the base added 500 parking spaces—which currently require a shuttle to get to and from—and a Grand Hyatt hotel.

The new Keetley Express lift is Deer Valley’s first high-speed six-pack and first-ever bubble lift, extending from Deer Valley East to the base of the Sultan Express. The neighboring Hoodoo Express directly serves the beginner slope at Deer Valley East, running parallel the first 15% of the Keetley Express lift line. The final lift, the Aurora Quad, allows skiers to get out of a drainage near the base area back to the main part of East Village.

Complementing these new lifts is 19 new trails and 316 acres of terrain. As of the 2024-25 season, all of the new trails are rated beginner or intermediate, although several blue trails were consistently left ungroomed this winter (advanced-level trails will follow in future expansion phases). Notably, while the majority of new trails sit in lower-elevation areas near the new base, a handful extend from the top of Bald Mountain, providing a continuously skiable vertical descent of over 3,000 feet at Deer Valley for the first time in the resort’s history.

While multiple additional new lifts and trails are expected to open as part of Phase 2 next winter, we decided to check out the Deer Valley experience as it existed this season. So how do the new investments stack up? Let’s take a look.

The new Deer Valley Expanded Excellence terrain for the 2024-25 season, with the three new lifts highlighted in red. The nearby terrain shaded in light green is expected to open for the 2025-26 season.

Our Take

While it was explicitly designed with real estate in mind, the first phase of Deer Valley’s Expanded Excellence brings some surprising benefits. The new terrain offers a beautiful natural aesthetic, providing a welcome contrast from the built-up, artificial vibe that plagues much of the rest of Deer Valley. Views of the Jordanelle Reservoir are incredible, and the new trails feel thoughtfully designed for the topography, with some being very lightly gladed. As of the 2024-25 season, the new terrain might be the most scenic anywhere at Deer Valley—so we’re crossing our fingers that it doesn’t get overwhelmed by luxury real estate in the future.

Thanks to this year’s terrain expansion, Deer Valley offers continuously skiable terrain of over 3,000 vertical feet for the first time ever.

While this year’s expansion won’t be the most exciting for thrill-seekers, the terrain itself is still a big win for the Deer Valley in a number of ways. Previously, the resort’s on-paper 3,000-foot vertical drop didn’t translate into long, continuous runs; the rolling mountains elsewhere at the resort broke things up, requiring mid-mountain lift rides to complete a full top-to-bottom descent. However, the new trails from the top of Bald Mountain to the bottom of East Village offer a full 3,050-foot vertical descent, creating some of the longest uninterrupted ski runs in all of Utah and finally making Deer Valley an enjoyably skiable mountain for those who prefer long runs. While everything in the new zone is rated for beginners and intermediates, several of the blue trails were consistently left ungroomed this winter, offering a bumpy, more advanced experience.

As for the lifts: the Keetley Express is the clear highlight. With its bubble chairs and heated seats, it’s the first enclosed chairlift at Deer Valley (and second enclosed lift in total following the Jordanelle Gondola), making for an especially comfortable ride on frigid days. The Hoodoo Express runs alongside the Keetley lift throughout beginner zone, providing access to a much more logistically practical and isolated learning environment than that of the Snow Park base. Due to the layout of the trails, the Hoodoo lift provides the only access to this learning area; it is discontiguous from the upper mountain runs, meaning guests will not need to worry about more aggressive skier traffic from elsewhere at the resort.

The Keetley Express, which provides the primary access to this year’s expansion terrain, is both Deer Valley’s first bubble chair and its first six-pack. The neighboring Hoodoo Express (pictured left) provides access to an isolated lower-mountain learning area.

Finally, it’s worth touching on the Aurora lift, which is a fixed-grip quad. But while fixed-grip chairs are known for their slow run speeds, the Aurora lift is so short that the slower speed doesn’t really detract from the experience. In fact, the entire ride takes less than two minutes.

But for all the promise, the East Village area is still very much a work in progress. Construction is ongoing, with at least three lift terminals still unfinished and the base village in a fairly rudimentary state by Deer Valley’s normally polished standards. That said, we have to give credit where it’s due: the porta potties might be the nicest we’ve ever seen at a ski resort.

The unfinished lift terminal of the Galena Express at Deer Valley this February. Later on this season, quad chairs were added to the line.

There are also a few logistical quirks that will likely be resolved in future years, but created some headaches this winter. The Sultan Express area is a bottleneck right now, with all guests coming from the East Village base needing to funnel through that lift to get elsewhere on the mountain (there will be redundancies built in future seasons). And while the East Village parking is plentiful, having to take a shuttle to the base makes for a less-than-seamless experience. Thankfully, future development includes a more direct connection between the parking and the lifts. Another funny circumstance resulting from this multi-year expansion: a few signs currently point toward trails that haven’t officially debuted yet, including some black-diamond trails that are expected to be quite a bit harder than anything that debuted this winter.

As the only lift providing access out of the East Village terrain area, the Sultan Express chair was a huge chokepoint this winter. New lifts for the 2025-26 season are expected to address this bottleneck.

But perhaps the biggest issue with Deer Valley’s expansion terrain might be snow reliability. With most of the new terrain sitting below 7,500 feet and facing east, natural snow retention is quite a bit less reliable than most other parts of the resort. While strong snowmaking kept this year’s trails in reliable shape throughout the bulk of this season, it was clear that the areas just off the marked trails were hurting for cover throughout certain parts of the season. Some of the non-groomers were quite icy when we visited, but higher-elevation bump runs stayed soft.

Overall, this first phase is a strong leap forward for Deer Valley. It doesn’t exactly cater to the most advanced skiers out there, and natural snow reliability could be better—but for intermediates and those seeking scenic, comfortable laps (i.e. Deer Valley’s typical clientele), it’s an exciting addition. And with exponentially more terrain and infrastructure expected to come next winter (the resort claims it is opening an astounding 91 new trails across approximately 2,900 acres of terrain next winter), this year may only be a small taste of what yet to come.

Considering a ski trip to Utah next winter? Check out our comprehensive Utah ski resort rankings, as well as our Deer Valley mountain review from this past season. You can also check out our analysis on the ski patrol strike and other compounding factors facing the Utah ski scene in our video analysis below.

What I Learned From Building PeakHouse This Season (And Where We’re Going Next)

The PeakHouse program has grown more than I could have ever anticipated over the past 12 months—and we have you to thank for that. Well, this post is going to be different. Taken on Day 2/46, picking up groceries for PeakHouse Colorado! Starting […]

Mountain

The PeakHouse program has grown more than I could have ever anticipated over the past 12 months—and we have you to thank for that.

Well, this post is going to be different.

Taken on Day 2/46, picking up groceries for PeakHouse Colorado!

Starting today, I’m going to be writing you a little more personally from time to time—pulling back the curtain on what’s happening behind the scenes at PeakRankings and what’s coming next. At the heart of all this is community. PeakHouse exists because of the connections we’ve built together, and I want to make sure we’re creating space to keep those going outside of the mountains. (If you haven’t already, you can join our growing Circle community space here!)

I’m writing this after being away from home in Brooklyn for 46 straight days, leading PeakHouse trips across Colorado, Montana, Wyoming, Austria, and Switzerland—without a single break to see friends or family in between. It was an absolute whirlwind. Interest in the PeakHouse program exploded after our original Utah trip in March 2024. Naturally, my instinct was to meet that demand head-on. We went from hosting one winter trip in 2024 to running six this season—a massive leap, but one we felt was worth it.

Personally, this season also marked a big shift. As someone used to solo travel for ski reviews and content, having a group along for the ride made the time pass by so much faster. There’s something transformative about experiencing an adventure with others instead of going it alone.

There were so many standout moments this season that it’s hard to pick favorites—but a few will stick with me for a long time.

In the Dolomites, Rick led us on a mission to a hidden, horse-drawn surface lift he remembered from a prior trip. It took nearly four hours of skiing from our base village just to reach it, but the journey (and the throwback lift) was 100% worth it.

These horses dragged about 50 of us up the slope at a time. It was absolutely sick.

In Colorado, Jacob—who happens to be a professional baker—whipped up fresh focaccia bread for the house one night. It made its way into everyone’s lunch pack the next day and set a new bar for PeakHouse meals going forward.

Jacob’s focaccia before it made it into hungry PeakHouse Colorado mouths.

And the entire Northern Rockies crew? Absolute savages.

Every single day, they took on the steepest hike-to terrain we could find—and did it with the kind of energy and stoke that reminded me why this program exists. I can’t think of another time where a group of 20 was ripping it up the bootpacks and sending it down the chutes.

Some of the PeakHouse crew at the top of the Jackson Hole Headwall hike! Everyone here did at least five more hikes before the end of the trip.

Finally, I want to give a personal shoutout to some of the people who’ve come back for their second trip: Sean, Will, Josh, Grant, Adi, Oscar, Brian, and Bill. And an extra huge shoutout to Steve, who came back for round three. Your continued trust and support means the world, and you’ve helped shape this community into what it is today.

But let’s be real: being on the road for a month and a half isn’t easy. I missed birthdays, family moments, and the rhythm of daily life in New York. That’s why we’re already investing in more trip leaders—so the program can grow without me needing to be everywhere at once. Huge shoutout to Sam Daley, who led the Mammoth trip this March. It was the first PeakHouse I didn’t personally attend, and based on feedback, he absolutely crushed it.

The PeakHouse Mammoth crew!

While the ski season in North America might be winding down, this is just the beginning for what’s ahead. I invite you all to join us on an international ski trip to New Zealand in August and our first ever National Park trip to Banff in July.

To the 100+ of you who’ve joined us on a PeakHouse trip so far: thank you. Your support means the world. I can’t wait to see what we’ll build together next.

Talk soon,

Sam

Founder & CEO, PeakRankings

P.S. I’d love to hear from you. Whether you’ve been on a PeakHouse trip, are thinking about joining one, or just have thoughts on where we should take things next—hit reply and let me know. I read every message.

Ski Lifts Explained: Basic Chairs to Engineering Marvels

When you visit a ski resort, one of the most critical aspects of your skiing or riding day is how you get up the mountain. Ski lifts are the workhorses of these resorts, providing skiers and snowboarders with access to the slopes. However, not […]

Mountain

When you visit a ski resort, one of the most critical aspects of your skiing or riding day is how you get up the mountain. Ski lifts are the workhorses of these resorts, providing skiers and snowboarders with access to the slopes. However, not all uphill transportation at ski resorts is the same.

Mountains employ various types of transportation contraptions, each with its own unique features, advantages, and drawbacks. In this video, we’ll take a closer look at the different types of lifts commonly found at ski resorts, including their capacities, speeds, and the pros and cons of each one. Let’s jump in.

Surface lifts, such as T-bars, are often used in more wind exposed areas, such as areas above the treeline.

Surface Lifts

Let’s start out with the most rudimentary of all ski lifts, the surface lift. These were the first motorized lifts to make their way into the ski world when the sport was born in the early 20th century. Many of you probably haven’t even thought of surface lifts as real lifts, but they play an important role in uphill transportation in several circumstances.

There are three main types of surface lifts:

T-Bars and Platter Lifts

T-bar and platter lifts consist of a horizontal bar or platter attached to a moving cable. Skiers or snowboarders grab onto the bar, and it pulls them uphill. Platters typically accommodate one rider, while T-bars typically accommodate two.

Rope Tows

Rope tows are similar to platters, but use a continuous loop of rope instead of a bar. Skiers and riders hold onto the rope as it moves uphill, providing tension for the ride.

Magic Carpets

Magic carpets are conveyor belt-like lifts that are often used in beginner areas. Riders stand on a moving carpet that takes them uphill, meaning that unlike T-bars, platters, and rope tows, riders do not have to exert real physical energy to ride them. They are particularly user-friendly for beginners and small children, but they are also the slowest of the bunch, and as such, really only get used for very short distances.

Carpet lifts are often found in beginner areas, or bunny slopes, and provide an easy way to get up the mountain.

Surface lifts have a couple of notable advantages despite their simplicity. First, they are easy to operate and require minimal infrastructure, making them far more cost-effective to install and maintain than chairlifts or gondolas. Their simple design allows them to be used on sensitive terrain, such as glaciers, where full-size towers would be infeasible. In addition, surface lifts are often easier to unload than chairlifts, especially in beginner-oriented areas, and some variants can operate at faster speeds than certain chairlifts, making them faster alternatives to get up the mountain. Finally, surface lifts offer far better wind and weather resilience than traditional lifts, as their lighter, ground-oriented footprint creates more stability when storms roll around—and allows riders to hypothetically get off the lift at any time in case of an emergency.

But with a lift type this rudimentary, you run into some limitations. The biggest drawback might be capacity; since surface lifts can only carry one or two individuals at a time, guests will experience longer wait times during peak times at busy resorts. In addition, surface lifts become a lot less practical as ski slopes become longer and steeper, with the physical toll of riding platters, rope tows, and T-bars growing substantially more burdensome as the gradient and ride time increase. In today’s world, you probably think of a ski lift as an opportunity to relax and recharge—but what if it actually becomes the most exhausting part of your day?

Surface lifts are about as straightforward as ski lifts get, but there’s a reason why ski resorts that can afford to have moved onto more complex and higher-capacity uphill transportation.

Fixed grip lifts are incredibly common at more regional ski areas, and their incredibly long lifespan means you could be riding on lifts that are up to 70 years old.

Fixed-Grip Chairlifts

When it comes to the actual chairlifts you probably picture at a ski resort, fixed-grip chairlifts are arguably the most basic and traditional form. These lifts feature chairs that are permanently attached to the cable. Passengers load onto the lift while it’s moving at a constant speed, meaning the lift does not slow down at the bottom or top terminals. Fixed-grip chairlifts are cost-effective to install and maintain, making them common at smaller resorts and beginner slopes. Most often, resort guests will find them in two-to-four passenger configurations, although variants ranging from single occupancy to six-pack exist.

Some newer fixed-grip chairlifts are now paired with loading carpets, which help regulate passenger entry by slightly accelerating riders before they reach the chair. This makes the loading process a bit smoother and sometimes allows the lift to run at a slightly higher speed than a traditional fixed-grip chair, although other more complex types of lifts are still usually easier to load and faster.

Thanks to their lower cost and easier maintenance, fixed-grip lifts are often used for shorter lift routes, as backups for more popular lifts, or in terrain areas with variable opening schedules where a higher-cost lift wouldn’t be justifiable. Lower-capacity fixed-grip chairs, typically doubles or triples, are often employed in expert-oriented areas to subtly discourage less-experienced guests from riding them. In addition, fixed-grip chairlifts have smaller terminal footprints than their higher-end counterparts, meaning that they can be fit into far more complicated or space-constrained areas.

But fixed-grip chairlifts come with significant drawbacks, the biggest of which is arguably their speed. Because they must run slowly enough for safe loading and unloading, fixed-grip lifts maintain a leisurely pace on the way up the mountain. In fact, a standard fixed-grip lift ride typically takes more than twice as long as a more modern experience. However, because fixed-grip lifts have to operate at a reasonable speed to maintain acceptable transport times, their loading and unloading process is much quicker than on modern lifts, which can be a challenge for less-experienced guests. This can make the ride even slower, as lift operators often slow down or stop the lift to assist struggling passengers. While some skiers and riders may find the slower ride time okay as a chance to recover between runs, other guests will find it frustrating—especially on cold, windy days when prolonged exposure to the elements makes for an uncomfortable experience.

While fixed-grip chairlifts may not offer the convenience and speed of detachable lifts, they remain a fundamental part of many ski resorts. Even the fanciest ski resorts still employ them in some capacity, with these simple lifts providing a reliable and affordable means of getting skiers and snowboarders up the mountain.

Detachable lifts, also called high-speed, or express lifts, are some of the most common lifts you’ll find at a destination ski resort.

Detachable Chairlifts

For most guests at a ski resort, the first lift they’ll truly look forward to riding is a detachable chairlift.

Detachable chairlifts, also known as high-speed or express lifts, are designed so that their chairs can detach from the moving cable at the base and top terminals. This allows for much slower loading and unloading while the cable itself continues moving at high speed. As a result, these lifts not only transport skiers and snowboarders uphill significantly faster than fixed-grip chairlifts, but they also make for a much more convenient loading and unloading experience, enabling quicker mountain laps and greatly improving the experience for the average guest. In beginner and intermediate-oriented areas, having a high-speed lift can greatly reduce misloads, resulting in fewer lift stoppages throughout the day. Some of the highest-end detachable lifts even feature heated seats and protective bubbles to shield passengers from wind and cold temperatures—comforts rarely, if ever, found on fixed-grip or surface lifts. Detachable chairlifts typically come in four-to-six-passenger configurations, although variations range from doubles to eight-packs.

Thanks to their speed and efficiency, detachable chairlifts have become essential for any ski resort hoping to stay competitive. However, because of the mechanics of their terminals, the chairs must be spaced farther apart than on fixed-grip lifts. This means that unless a detachable lift has a higher-capacity chair (i.e. a six-pack versus a quad), it won’t necessarily move more people per hour than a fixed-grip lift, notwithstanding the misload benefits we mentioned earlier. Another drawback is that detachable chairlifts have a shorter lifespan than their fixed-grip counterparts. While fixed-grip lifts can remain operational for many decades with proper maintenance, most high-speed chairlifts have required replacement after 30 to 40 years due to mechanical wear. Finally, detachable chairlifts are more susceptible to ice and wind-related downtime than fixed-grip and surface lifts. Gusty wind conditions can interfere with safe and properly-aligned grip engagement at terminals, while any ice buildup needs to be cleared from the cable, grips, and terminal interiors to ensure the chair detachment and reattachment process functions smoothly.

High-speed chairlifts may not be perfect at everything. But as uphill transport for an activity that revolves so much around cold weather, they provide an ideal and efficient solution.

Gondolas provide exceptional uphill capacity, and are often used for out-of-base lifts at destination resorts.

Gondola Lifts

But what if you want to shield yourself from the cold weather entirely? That’s where gondolas come in. Gondola lifts are characterized by wholly enclosed cabins that are suspended from an overhead cable, allowing for what’s essentially full isolation from the elements. Not only do gondolas offer a more comfortable ride than non-bubble chairlifts, but they are often warm enough to help visitors regain body heat—rather than lose it—before their next run, providing a much more efficient alternative to warming up in a lodge on a cold day. Traditional gondola cabins can typically fit more people than a chairlift, with most coming in six-to-ten passenger configurations, although variations ranging from two-to-fifteen passengers exist as well.

Thanks to their enclosed design and smoother ride, gondolas are often used for longer uphill spans where a chairlift ride—even a detachable one—might be too exposed and uncomfortable in cold or windy conditions. Their enclosed cabins also make them preferable for routes with high spans or downhill sections, which can be unsettling for guests with a fear of heights. At resorts that have them, gondolas are especially popular as transport from base areas, allowing skiers and riders to board before strapping on their equipment.

But while gondolas offer a highly comfortable experience, they come with tradeoffs that make them less practical in certain situations. Unlike chairlifts, where guests can simply ride up with their gear on, passengers must remove their skis or boards before boarding a gondola and either carry them inside or place them in designated exterior racks. This extra step makes gondolas less desirable for shorter rides or terrain zones that are frequently lapped, as the time spent removing and reattaching gear can offset the benefits of the enclosed cabin. In addition, some smaller gondola cabins can feel a bit claustrophobic, especially at the handful of resorts that still have four-passenger models.

Despite these drawbacks, gondola lifts remain a staple at high-end ski resorts, offering a comfortable, high-capacity alternative for accessing terrain where chairlifts may not be ideal.

Cabriolet lifts are basically open-air gondolas, and they are typically found in base areas. The lack of seating makes long rides uncomfortable.

Cabriolet Lift

A rare variation of the gondola is the cabriolet lift, which functions similarly to a gondola but features open-air cabins instead of enclosed ones. Cabriolet lifts are most commonly found in ski resort base areas, transporting guests from parking lots or village centers to the main ski area before they’ve had a chance to put on their skis or snowboard. Unlike gondolas which have seating, cabriolet lifts are designed for standing only. Because they lack the full enclosure and seating of traditional gondolas but still have the same practical drawbacks, they’re not really ideal for truly riding up the mountain, but they provide an efficient and scenic way to move guests around resort villages.

Chondola Lift

Another rare lift variation is the chondola lift, which consists of both chairlift and gondola carriers on the same ropeway. These lifts provide unique versatility, allowing guests to choose between the convenience of a chairlift and the comfort of a gondola cabin. However, due to their complexity, chondolas are expensive to install and come with a few drawbacks. Guests need to choose between separate loading lines for chairs and gondola cabins, which can lead to uneven wait times, as there are usually fewer gondola cabins than chairs. Additionally, because gondolas require slower speeds for loading and unloading, the entire lift must run at a lower terminal speed than a traditional detachable chairlift.

Pulse Lift

Finally, perhaps the least-known and least-understood type of gondola lift is a pulse gondola. Unlike a standard detachable gondola, where each cabin moves continuously along the cable, a pulse lift operates with groups of cabins that are fixed to the cable but move in clusters or “pulses.” These odd-looking lifts slow down at loading areas before speeding up again to a regular detachable speed once the journey starts. However, because multiple cabin clusters operate along the ropeway, pulse lifts need to slow down to a crawl whenever other cabin clusters reach the terminal to load or unload passengers. On longer applications, this can happen multiple times mid-ride. This makes pulse lifts incredibly impractical for anything more than short travel distances or very low demand applications where the resort can get away with only a handful of clusters.

While not as seamless as a fully detachable system, pulse lifts provide a practical compromise for resorts that need a high-speed lift but are okay with trading intermittent stops and capacity for minimized cost. In extremely rare cases, pulse chairlifts exist as well.

Aerial tramways can carry a large number of passengers at once, but the long headways between cabins mean the actual uphill capacity is quite low.

Aerial Tramways

But for some of the world’s most intense ski resorts, regular circulating ski lifts won’t cut it. That’s where aerial tramways come in.

Trams are a unique type of lift system that consists of large cabins suspended from thick cables, transporting passengers up and down the mountain in a single, continuous trip. Unlike gondolas, which have multiple cabins that circulate along a continuously moving cable, trams typically operate with just one or two cabins traveling back and forth on a fixed cable. Most trams can accommodate substantially more people per cabin than a gondola, typically carrying between 50-150 people per cabin, although variations between 5 to 200 people exist as well. In the craziest applications, even some double-decker cabins have been used.

Because of this design, trams are known for their ability to traverse extremely steep and rugged terrain with minimal support towers, making them an excellent choice for ski resorts that need to move guests over dramatic elevation changes or across deep valleys. Many of the world’s most iconic ski areas, including Jackson Hole, Snowbird, and Chamonix, have trams that provide access to their highest and most extreme terrain. Trams tend to provide some of the most scenic rides of any lift type, as their dramatic terrain spans lead to stunning views of the mountains they ascend.

One of the other primary advantages of aerial trams is their stability in high winds compared to gondolas or chairlifts. Since most tram cabins are connected to thick track cables rather than relying on a single haul rope for support, they sway less in strong gusts, allowing them to operate in conditions that might shut down other lifts. Finally, aerial tramways can move at significantly faster speeds than even high-speed chairlifts and gondolas, with the fastest trams able to achieve operating speeds of up to 26 mph (12 m/s), which is over twice that of its circulating ropeway counterparts. This can be of significant benefit for particularly long lift route stretches.

However, despite these advantages, aerial tramways have significant downsides—the biggest being their low capacity. Since most trams can only carry between 50 and 150 people per trip and operate on a fixed schedule rather than continuously, they tend to involve long lift lines, especially at peak hours. Unlike gondolas or high-speed chairlifts, which continuously load passengers, trams require all guests to wait for the next scheduled trip, meaning a single missed ride can result in an extended delay.

Another disadvantage of trams is that, like gondolas, passengers must remove their skis or snowboards before boarding—although the headways between each tram car make this somewhat of a secondary issue. Finally, tram rides can feel crowded and less comfortable, especially when cabins are packed to full capacity on busy days.

Despite these drawbacks, aerial tramways remain a staple at many major ski resorts due to their ability to access extreme terrain, their durability in high-wind conditions, and the unparalleled mountain views they provide. While they may not be the most efficient lift type for moving large crowds, their ability to reach rugged, high-altitude terrain—and gatekeep crowd levels on extreme terrain—ensures they remain an important part of big mountain ski resort infrastructure.

Tricable gondolas, or 3S gondolas, have all the upsides of Aerial Tramways, but much higher capacities. However, their incredibly high cost makes them a rare sight at ski areas across the world.

Tricable Lifts and Funitels

But what if a chairlift or gondola isn’t sufficient to navigate the terrain a resort might need to cover—and you also need higher uphill capacity than a tram? That’s where specialty lifts like tricable ropeways and funitels come into play. Both systems offer significantly improved wind resistance and tower span capabilities over traditional lifts without the practical drawbacks of a fixed tramway. Thanks to their reinforced cable systems, these lifts can also support larger cabins than traditional gondolas, typically carrying between 20 and 30 passengers per cabin, although the presence of multiple cabins on the rope means they aren’t as big as trams.

Tricable gondolas, also called 3S lifts (from the German word for “three cables”), use two stationary support cables and a third moving haul cable. This particularly stable design allows these lifts to span significantly longer distances with fewer towers, making them ideal for ski resorts that need to move large numbers of guests between far-apart resort areas or over rugged terrain where tower placement is impractical. While incredibly complex to construct, these lifts dramatically improve guest flow and provide access to terrain that would otherwise require multiple conventional lifts or an inconvenient detour.

Funitels utilize two moving haul ropes, which provide reduced cabin sway and incredible wind resistance.

Unlike a tricable ropeway, which features two fixed support cables and one haul cable, funitels use two parallel haul cables that grip the cabins at two points instead of one. This double attachment system creates outstanding wind resistance, reducing cabin sway and allowing these lifts to function in wind speeds that would almost certainly shut down everything else. This has made funitels especially popular in high-alpine terrain with significant exposure. Because funitels prioritize wind resistance over long-span capability, they are less commonly used in areas requiring exceptionally wide tower spacing.

Like traditional gondolas, 3S and funitel lifts have trade-offs, though their challenges differ slightly. Guests will have to remove their equipment to ride them, and because their cabins are so big, exterior equipment racks rarely exist. Also, these lifts sometimes lack seating for all passengers, meaning at least some guests will have to stand up if the cabin loads to capacity—this is especially the case when it comes to funitels.

But the biggest drawback for these specialty lifts is arguably their price tag. These lifts cost exponentially more than a traditional gondola, and there’s a reason why only a couple dozen of each exist worldwide, almost exclusively at the world’s highest-end mountains. Even the most cash-rich resorts are incredibly particular about where and when they install these lifts, making sure they put them in the places with the highest winds and most difficult terrain layouts where conventional lifts simply wouldn’t suffice.

A few ski areas, most notably in Europe, have rail-based uphill transportation.

Mountain Railways

But sometimes, ski resorts face such exceptional circumstances that using a cable-driven system just doesn’t make sense. This is where mountain railways come in. These distinctive uphill constructions are found almost exclusively in Europe, although a handful do exist at resorts elsewhere around the world. The two main types of mountain railways used as ski lifts are cog railways and funiculars, each serving a distinct role in transporting skiers and riders efficiently and reliably.

Cog Railways

Cog railways, also known as rack railways, are a unique type of train system that uses a toothed rack rail between the running rails to help trains climb steep inclines that regular trains cannot handle. Because they run on fixed tracks and achieve much higher speeds than any other type of ski lift, cog railways are incredibly efficient, with individual trains far exceeding the capacity of any chairlift or gondola.

Funiculars

A funicular railway is another form of cable-driven mountain transport that operates on fixed rails, typically using two counterbalanced train cars moving in opposite directions. Unlike cog railways, which use a toothed rack for traction, funiculars rely on a pulley system to pull one cabin up while lowering the other down. They are particularly valuable in avalanche-prone or high-wind areas, where traditional chairlifts and gondolas might be unreliable.

Funiculars vary widely in design. Visitors can find installations ranging from short-distance, 4-person lifts that are basically just glorified elevators to massive resort transport systems capable of moving up to a whopping 440 people per trip at speeds comparable to cog railways.

Due to their incredibly fast travel speeds, mountain railways can be just as efficient as circulating ropeways, even with longer headways between departures. Additionally, alpine railways provide a comfortable, enclosed ride with no exposure to the elements, making them an attractive option for skiers and riders looking to stay warm on the way up.

However, the biggest limitation of mountain railways is their reliance on dedicated tracks. This either reduces usable ski terrain, requiring careful placement to maintain skier and rider access, or demands expensive tunnel construction to avoid interfering with slopes. Additionally, unlike chairlifts or gondolas, which continuously load passengers, cog railways and funiculars operate on a fixed schedule—meaning a missed departure could result in a long wait.

Ski trains are far from the most practical option for most ski resorts, but they’re among the most comfortable and novel forms of uphill alpine transportation. For many, riding one of these railways will be just as unique of an experience as visiting the ski slopes themselves.

While they’re typically used for grooming slopes, Snowcats can be found at a few ski areas being used for uphill travel, though they often come with extra costs.

Snowcats

But in certain cases, ski resorts face terrain where operating a lift or railway does not make practical or financial sense—but they still want to offer a way to transport guests uphill. That’s where snowcats come in. While primarily designed for grooming ski slopes, snowcats are also used as a specialized form of uphill transportation in certain scenarios. Cat skiing operations, typically found in remote resort areas or organized as guided experiences in true backcountry areas, transport small groups of skiers and snowboarders to seldom tracked terrain that is otherwise inaccessible by traditional ski lifts. In rare cases, some ski resorts utilize snowcats as alternative transportation when lifts are closed due to mechanical issues, avalanche mitigation, or extreme weather.

Since most cat skiing operations rely on a single snowcat carrying just 5-15 passengers per trip, uphill capacity is by far the lowest of any type of ski resort transport, with untracked powder being a common sight at the top of these rides. Due to their high operating costs and extremely low capacity, resorts often charge an extra-cost add-on for guests to ride these cats, although this is not the case 100% of the time. If a snowcat isn’t at the loading area when they arrive, guests may have to wait quite a while to ride it.

While snowcats are far less efficient than traditional ski lifts and offer limited capacity per trip, they provide a rugged, adaptable solution for reaching terrain that would otherwise be off-limits without hiking—and often has some of the best powder that’s accessible in-bounds within the resort.

Final Thoughts