Hooray it’s Labor Day

Holiday Weekend Insights Saturday –Check out the S.T.E.M activities under the Adventure Tent. There are two chances to play with the Water Rockets and take the challenge of the Space Landing. Water Rockets blast off at 9:00 am and again at 10:30 am. The Space […]

ViewsImpressive Prominence

Conditions & Atmosphere Weather: Mostly Sunny, with a high near 67. West wind 6 to 8 mph, with gusts as high as 20 mph. Vibes: We have entered our last week of full summer programming here at Smuggs. The calendar says end of August, but when I […]

ViewsTurn Me Loose

Conditions & Atmosphere Weather: Sunny, with a high near 78. Calm wind becoming north around 5 mph in the afternoon. Vibes: Walk me out in the morning dew today, and if your feet get a little wet, it doesn’t matter anyway. It’s a sweatshirt morning that’s going […]

Views

Ikon Pass Reservations Are Live As of August 4. Should You Commit Now?

Ikon Pass mountains such as Jackson Hole require reservations for lift access for the upcoming season. If you have an Ikon Pass product for the 2025-26 season, you may need to make in-advance reservations for lift access to certain resorts. This reservation system […]

Mountain

Ikon Pass mountains such as Jackson Hole require reservations for lift access for the upcoming season.

If you have an Ikon Pass product for the 2025-26 season, you may need to make in-advance reservations for lift access to certain resorts. This reservation system opened up on August 4, 2025, allowing guests to start securing spots at participating mountains. But with many of Ikon’s most popular mountains requiring these reservations, do you need to commit now to secure your spot? In this piece, we’ve compiled all you need to know about Ikon’s reservation system—and whether you should rush to figure out your itinerary if you haven’t already.

Which Ikon Pass mountains require reservations for lift access?

The following Ikon resorts will require reservations for the 2025-26 season:

Reservations are no longer required at:

The following resort is no longer on the pass for 2025-26:

Which Ikon products does this policy apply to?

All Ikon products, including the full Ikon Pass, Ikon Base and Base Plus Passes, and Ikon Session Passes, require reservations at the aforementioned mountains.

Do you need to book your reservations on August 4 to secure your spot?

No—if previous seasons are any indicator, reservations to these mountains will not fill up on day one, even at the most popular mountains on the busiest days. But if you already have your vacation booked, there’s no harm to securing your reservation now so you don’t forget to do so later.

When will Ikon Pass reservations really start to fill up?

Based on previous years, we expect that Ikon Pass reservations will start to fill up by the middle of the fall. Holidays and peak weekends at top-tier destinations such as Jackson Hole and Aspen will be the first to go, with the other destinations following shortly after.

For the most hassle-free experience, try to secure your reservations before mid-October, assuming you are visiting on a weekend or holiday. That said, if you plan to visit these mountains on off-peak weekdays (i.e. Monday through Thursday on a non-school vacation week), you may be able to wait until the day of to book your reservation.

If a reservation date is completely full, is there any chance it will open up?

Yes—if you check back religiously, chances are you can snag a spot, even if your date has already filled up. Others may cancel their reservations, or resorts may open more spots depending on expected snow conditions.

However, if you don’t want to deal with the stress of being in this situation and checking the Ikon website four or five times per day, it’s best to secure your reservations early.

Can you cancel your Ikon Pass reservations if you decide you don’t want to ski/ride on a particular day?

Yes, you can cancel your reservations up until 9am the date of your visit with no penalties. So even if you aren’t 100% sure of your itinerary, it may be a good idea to secure your spot now, and revisit later if need be.

It’s worth noting that if you do not show up or cancel after that time on the date of your reservation, you may be restricted from making or taking advantage of future reservations.

Is there a limit to the number of Ikon reservations one can make at a time?

Yes—passholders can only make reservations for up to the number of dates of access they have at each mountain—meaning seven for each mountain with the full Ikon Pass, five for each mountain with the Ikon Base and Base Plus Passes, and two to four total depending on the Ikon Session Pass product (none of the reservation-mandating mountains offer unlimited access on Ikon).

As a result, passholders can’t “over-reserve” if there are a lot of potential dates they want to secure spots for.

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, Ikon passholders won’t need to scramble to secure their reservations on August 4 for access to Jackson Hole, Aspen Snowmass, and other popular resorts. But these reservations will begin to fill during the fall for peak weekends and holidays, and while spots do open up sporadically, passholders will save themselves a lot of hassle by booking reservations as early as possible. If you’re not 100% sure of your itinerary, you can always cancel your reservations up until the day of with no penalty!

Not sure of whether the Ikon Pass is right for you? Check out our in-depth comparison between the Ikon, Epic, Mountain Collective, and Indy pass products. Additionally, you can check out our Ikon Pass mountain reviews here.

Why Oregon’s Ski Industry Is in Big Trouble

Resorts like Mount Hood Meadows are at risk of a complete shutdown within the next 12-18 months due to an escalating liability crisis. Background When it comes to skiing and riding in the United States, the state of Oregon has long been a […]

Mountain

Resorts like Mount Hood Meadows are at risk of a complete shutdown within the next 12-18 months due to an escalating liability crisis.

Background

When it comes to skiing and riding in the United States, the state of Oregon has long been a strong regional choice for those in the Pacific Northwest. That’s why recent events in the state have been so alarming, with a business environment that has quietly become the most hostile in the country for ski resort operations. And due to developments in the state in recent weeks, there is a real possibility that every major ski resort in the state could soon be legally barred from opening.

So what’s exactly happened, and how likely is the so-called “nuclear” scenario to actually happen? Well, in this piece, we’ll go through the series of events that made Oregon uniquely susceptible to the crisis it currently faces, whether any other states have faced similar issues, and how the state could feasibly dig itself out of the hole it now finds itself in—despite the fact that it currently may not have the political will to do so. Let’s jump into one of the least known impending catastrophes in the American ski industry.

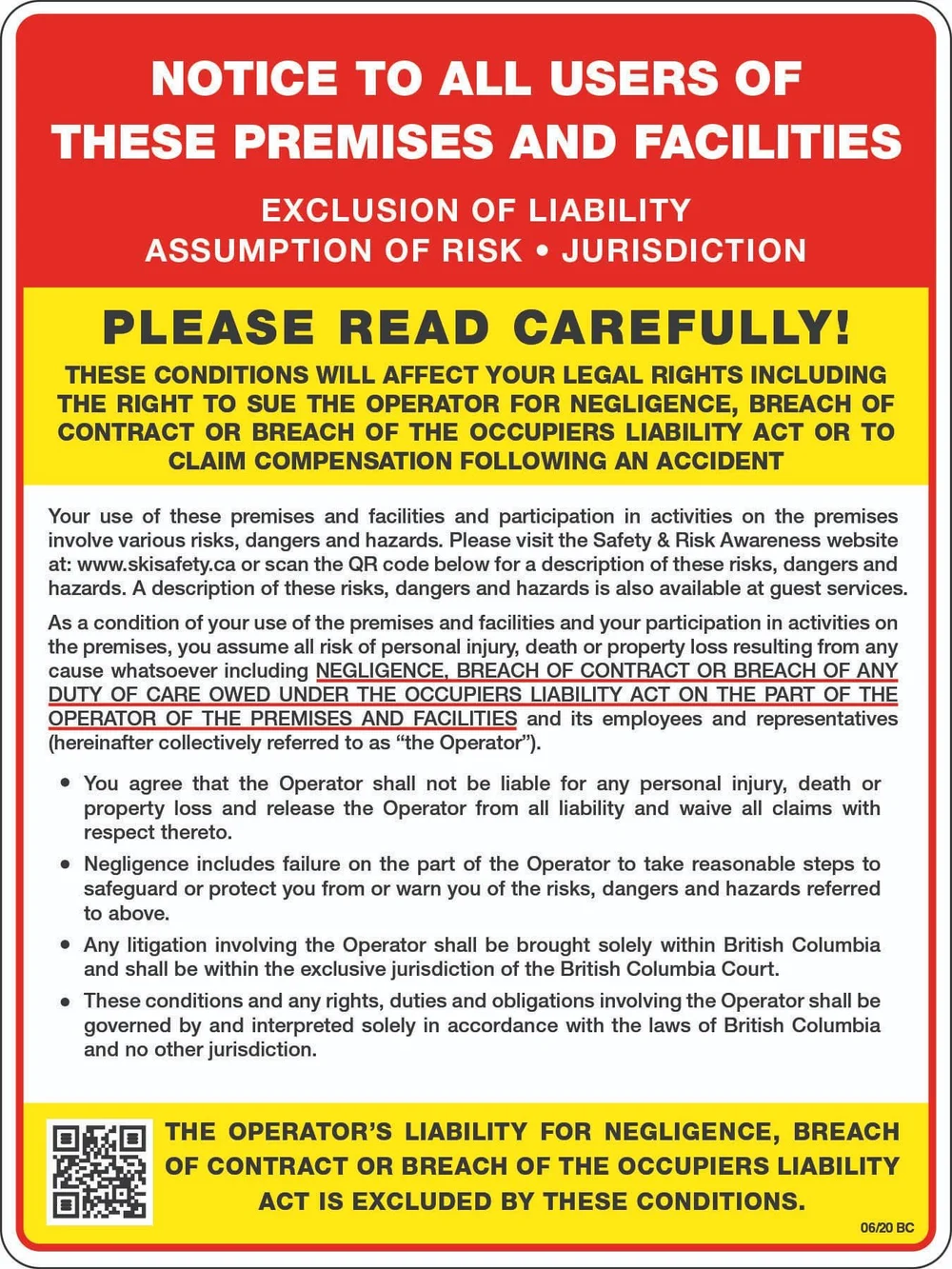

Liability waivers like this one have long protected ski resorts from catastrophic lawsuits stemming from high-risk activities.

Oregon’s Outdoor Liability Insurance Background

The crisis that Oregon currently faces primarily boils down to one factor: liability insurance. For many decades, ski resort liability insurance worked generally the same in Oregon as it did in other states. Liability waivers have long served as the legal backbone of the outdoor recreation industry, allowing ski resorts and adventure operators to function in high-risk environments without the constant threat of catastrophic lawsuits. In most Western states, these waivers are enforceable so long as they’re clear and voluntary, shielding operators from claims arising from “ordinary negligence”—think catching an edge, hitting a tree, or colliding with another skier or rider. This legal clarity gives insurers confidence, enables resorts to keep their premiums in check, and arguably helps keep lift ticket rates at practical levels too.

But in Oregon about a decade ago, a series of legal events completely upended all of that.

Bagley v. Mt. Bachelor: The Case that Shook the Foundations

In 2006, 18-year-old Myles Bagley was snowboarding at Central Oregon’s Mount Bachelor when he hit a jump in the resort’s terrain park. Unfortunately, the landing went horribly wrong. Bagley suffered a severe spinal cord injury that left him paralyzed from the waist down. He later argued the jump was defectively designed and unsafe.

Like most snowboarders and skiers, Bagley had signed a liability waiver when he purchased his season pass. The agreement released Mount Bachelor from responsibility for injuries, even those resulting from negligence. Despite this, Bagley filed a lawsuit, claiming the resort had acted recklessly in building the terrain feature.

What followed was a years-long legal battle that culminated in a landmark 2014 Oregon Supreme Court decision: Bagley v. Mt. Bachelor.

In a ruling that reverberated across the outdoor recreation industry, the court declared Mount Bachelor’s liability waiver unenforceable. The court determined the contract was both unconscionable and against public policy, effectively invalidating essentially every liability waiver used in the state at the time.

The justices emphasized three main points in their decision: (1) the waiver was a contract of adhesion—non-negotiable and imposed by a party with disproportionate power; (2) skiers and riders had no ability to modify the terms, and thus no meaningful choice, and (3) perhaps most critically, the waiver attempted to release the resort from liability even for its own negligent conduct. The court found these circumstances contrary to Oregon’s legal principles, arguing it disincentivized safety and violated the public interest.

On paper, the ruling was intended to preserve legal recourse for seriously injured parties. But unfortunately, it eventually became clear that the decision, while presumably well intentioned, had taken things a little bit too far.

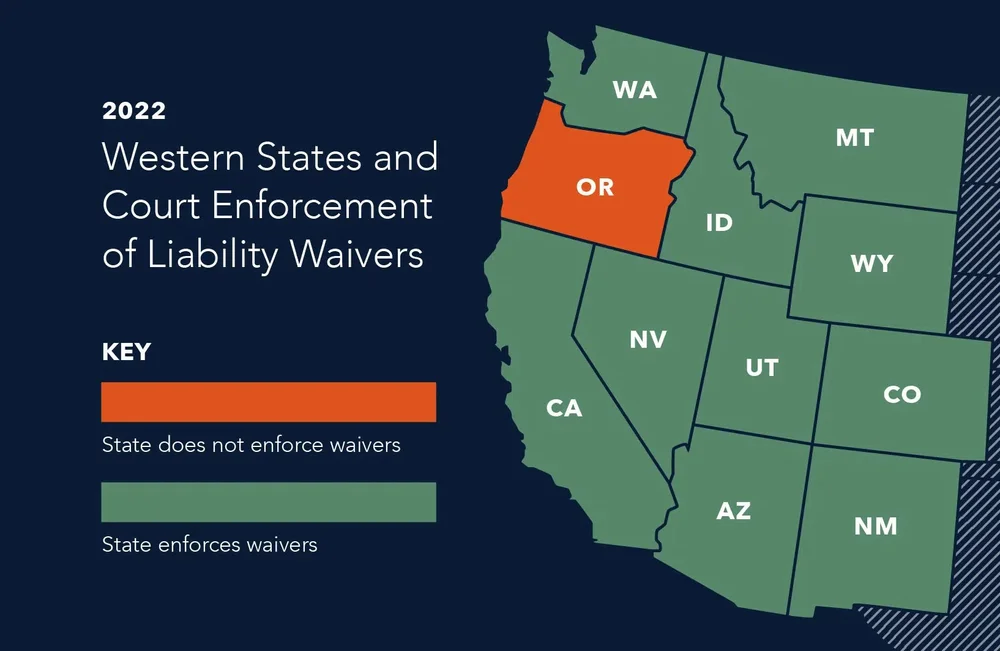

As of 2022, Oregon is the only Western state that does not enforce outdoor recreation liability waivers.

2014-2025: Lawsuits, Rate Spikes & Retreating Insurers

Over the next decade, Oregon’s ski industry entered a treacherous state. With liability waivers rendered largely unenforceable by the Bagley ruling, insurance companies began viewing the state as toxic territory. This came as injured patrons at ski resorts—and even summer recreation users—started suing more effectively, with damage demands climbing into the tens of millions.

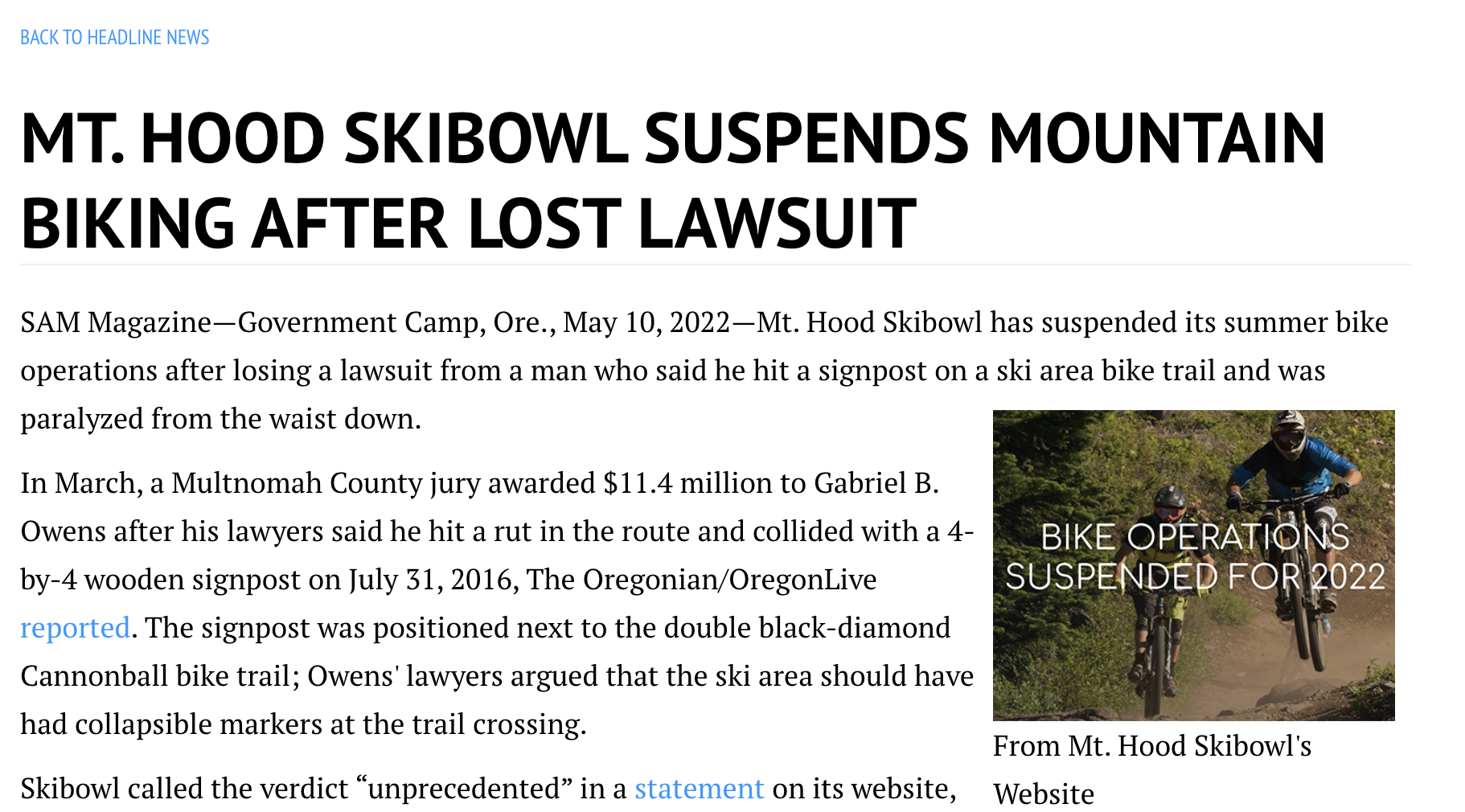

The first major post-Bagley case took shape in 2016, when a mountain biker at Mount Hood Skibowl was paralyzed after hitting a drainage rut and colliding with an unpadded wooden post along a downhill trail. Although the incident occurred during the summer, not the winter season, the case had major implications for the liability environment surrounding outdoor recreation in Oregon. In 2022, a jury awarded the rider over $11 million in damages, ruling that Skibowl had failed to take reasonable safety precautions despite signage and waiver protections. It was one of the largest single verdicts against a recreation operator in Oregon history, and in response, Skibowl completely shut down their bike park operations and hasn’t restarted them since.

Mount Hood Skibowl was forced to suspend its bike park operations in 2022 following an eight-figure lawsuit, and the mountain hasn’t restarted them since. Source: SAM Magazine

The legal risk wasn’t limited to Skibowl. Mount Bachelor also became a focal point for legal scrutiny, with two $15 million wrongful death suits following a pair of 2018 tree well fatalities, and a nearly $50 million claim filed after a child’s 2021 death after sliding into rocks on an icy run. Even community-oriented areas like Mount Ashland—despite facing no public lawsuits—reported being overwhelmed by rising insurance costs. The resort’s general manager noted a 129% increase in liability premiums over 12 years, with another 30% spike expected in 2025.

But it wasn’t just increasing premiums that occurred. By early 2025, brokers reported that fewer and fewer firms were willing to even consider underwriting ski resorts in Oregon. Outdoor recreation companies formed coalitions like Protect Oregon Recreation to plead for legal reform, warning that without enforceable waivers or other liability shields, the state’s entire outdoor recreation industry—not just ski resorts, but also including bike parks, rock gyms, and river rafting companies among others—was at risk. The insurance market was drying up, and fast.

Specifically when it comes to ski resorts, one potential indicator of these legal and financial pressures is how unpredictable Oregon’s terrain openings have become. Despite reasonably strong snowfall most seasons, resorts like Mount Bachelor and Mount Hood Meadows are consistently among the least resilient in terms of terrain access—and in a recent analysis, we ranked Oregon dead last for reliability among major ski regions. There’s no doubt that weather plays a major role here—Oregon’s maritime precipitation and volcanic geography can complicate slope cover and safe operations—but many in the industry believe the state’s legal environment only makes things worse. Resorts may be incentivized to act overly cautiously given the threat of excruciating lawsuits, keeping trails closed longer than necessary out of fear that a misstep could result in litigation. Anecdotally, the Summit Express lift at Mount Bachelor, which directly served the terrain where the 2021 death took place, was closed continuously for a period of approximately a month later that same season; it’s possible that conditions justified this closure, but this was an especially long suspension, even for this fickle terrain zone, and it’s easy to see the resort opting to err on the side of legal caution given the circumstances.

Mount Bachelor’s Summit lift, pictured above, operated significantly less reliably after a fatal accident that occurred on its terrain.

The Breaking Point: Safehold’s Exit and the Last Insurer Standing

So if it’s been over a decade since the Bagley ruling, why are we bringing all of this up now? In June 2025, the Oregon insurance situation went from precarious to existential. Safehold Special Risk, a major ski industry insurer that covered resorts like Mount Hood Meadows, Timberline Lodge, and Cooper Spur, announced it was pulling out of Oregon entirely. In doing so, it said Oregon had become unworkable: although the state accounted for only a fraction of its clients, it produced half of its $1M–$10M payouts.

That exit left Oregon with just one viable ski resort insurer: MountainGuard. MountainGuard, a legacy provider with national reach, has continued to serve the state—but not without concern. Its leadership made clear that a single massive verdict could force them to reassess. Should MountainGuard exit as well, no insurer may be willing to step in. And because without insurance, resorts can’t legally operate, this move would completely and immediately shut down every Oregon ski resort.

Legislative Attempts to Fix the Isssue

So given this pending catastrophe, has Oregon’s government made any efforts to address it? Well, at least claiming to recognize the growing crisis, Oregon’s state legislature has proposed several bills over the last decade, all aiming to restore partial legal protection for outdoor recreation operators.

In 2025, the most promising was Senate Bill 1196, which would have allowed liability waivers to cover ordinary negligence—but not gross or reckless misconduct. A similar House bill, HB 3140, had the same aim. Supporters said this was a common-sense compromise already in place in most other Western states. It would have brought Oregon in line with its neighbors while still allowing injured parties to sue in cases of gross negligence or willful misconduct.

The bills initially gained momentum. SB 1196 advanced through the Senate Finance and Revenue Committee, and lawmakers on both sides of the aisle signaled they would support the bill if it came to a vote. In fact, multiple state legislators and even Governor Tina Kotek indicated they would sign the bill into law if it passed the House and Senate.

But despite committee approval and apparent legislative support, neither SB 1196 nor HB 3140 were brought to a floor vote before the end of the 2025 session. Trial lawyer groups lobbied heavily against the reform, arguing it would strip injured parties of their right to sue and reduce incentives for resorts to maintain safe conditions. And in the end, legislative leadership declined to advance the bills to the floor, effectively killing them.

The failure was a huge disappointment for resort operators and insurance carriers alike. It marked the third time in ten years that similar legislation had failed in Oregon. And with this specific defeat, the state’s recreation industry moved to the precarious point at which it finds itself today. Indeed, Safehold had explicitly warned lawmakers it would exit the state if these reforms didn’t pass. When the bills died, Safehold made good on that promise—pulling out of Oregon and sending a clear message that the state would pay a steep price for its inaction.

If the last major insurer pulls out of Oregon, nearly all recreational activities will be forced to shut down immediately—and a solution may take awhile to materialize.

The Catastrophe: What Happens If the Insurance Disappears?

If Oregon’s last major ski insurer, MountainGuard, pulls out of the state, the effects would be both immediate and far-reaching.

Ski resorts that operate on Forest Service land, like Mount Bachelor, Mount Hood Meadows, and Timberline Lodge, are legally required to carry general liability insurance to maintain their permits. Without it, they’d be forced to shut down operations overnight. And that sudden stop wouldn’t just hit the slopes. Entire communities would feel the aftershocks.

Towns like Government Camp, Ashland, and Bend depend on consistent winter and summer visitation to support their tourism economies. Hotels, restaurants, gear shops, ski schools, and shuttle services would all be thrown into crisis. The liability issue stretches beyond skiing, too—rock gyms, rafting companies, zipline tours, mountain bike parks, and even climbing guides all rely on similar liability protections and insurance to stay afloat. If Oregon can’t find a fix, the state’s entire outdoor recreation economy could begin to unravel.

Central Oregon would be hit hardest. Over the past two decades, Bend has evolved from a modest town into a booming four-season destination, with outdoor recreation as the cornerstone of its growth. Its population has more than doubled since 2000, and a significant portion of its winter economy revolves around Mount Bachelor, Oregon’s biggest ski resort by a significant margin. While according to locals we interviewed, the resort struggled under mismanagement during what they called POWDR Corp’s “dark ages” in the mid-to-late 2000s, things turned around after POWDR infamously lost Park City and shifted its attention back to Bachelor, significantly boosting investment and bringing about a rebound in winter visitation.

A forced shutdown—triggered not by mismanagement but by insurance collapse—could send Bend into another economic slump. And since Bachelor operates a popular summer bike park, the fallout wouldn’t be limited to just ski season. Bend sees nearly twice as many visitors in summer as in winter, and the ripple effects of a shutdown would be felt year-round.

But if MountainGuard does leave, would the shutdown be permanent? Well, despite the catastrophic consequences in the interim, probably not.

A complete collapse of Oregon’s ski industry would force the state’s hand. While lawmakers have failed to pass legal reform in previous sessions, a full-scale closure would almost certainly bring enormous political pressure to act. We’d almost certainly see a fast-tracked bill to reauthorize liability waivers for ordinary negligence (something like SB 1196), and likely additional action through an emergency legislative session to get the industry back on its feet.

Still, a fix wouldn’t restore operations overnight. Insurers that have already fled the state may not return immediately, especially if legal uncertainty lingers. The state might have to lean on short-term solutions like government-backed risk pools or cooperative insurance programs. And even if those stopgaps work, rebuilding trust with national insurers could take years.

So while Oregon’s ski resorts might not be shuttered forever, the disruption would be deeply damaging—and the recovery could be long and uneven—for businesses and communities alike.

The nearby state of Idaho faced similar liability issues a few years ago, but government entities took initiative to correct course.

How Oregon Could Dig Itself Out: The Idaho Precedent

So has any other state ever faced something like this? Oregon’s path forward might seem uncertain, but it’s not without precedent. In fact, just next door in Idaho, the ski industry faced a similarly dire moment—and ultimately managed to stabilize the situation before it spiraled out of control.

The crisis in Idaho began in 2023, when the state’s Supreme Court allowed a wrongful death lawsuit against Sun Valley to proceed, despite the state’s long-standing Ski Area Liability Act. The case involved a skier who crashed into a snowmaking tower and suffered fatal injuries, and the court’s initial ruling opened the door to potential jury trials for incidents that had traditionally been considered part of the inherent risk of skiing. The decision sparked panic among resort operators, who feared a flood of litigation and a potential loss of insurance coverage. Bogus Basin even began adding extra signage around equipment purely as a legal precaution.

But in a rare about-face, the Idaho Supreme Court reversed course in mid-2025. The justices determined that because the hazard was clearly marked and padded, the skier had assumed the risk—meaning the resort was not liable under Idaho’s statute. The decision reinstated critical liability protections, and lawmakers are now working to clarify and strengthen the law further in the next legislative session. Just a few years earlier, Idaho also passed legislation upholding waiver enforceability for outfitters and guides, signaling a broader commitment to protecting the outdoor recreation economy.

The lesson for Oregon? Even when the legal foundation starts to crack, a coordinated response from courts and lawmakers can restore balance. While Oregon’s situation is further along than Idaho’s was—and arguably more severe too—there’s still a window for action.

Oregon’s ski resorts are facing several multi-million-dollar lawsuits that could come to a head within the coming months. Even one payout could move the last state insurer to pull the plug. Source: KATU

How Much Time Does Oregon Have to Act?

So just how long is this window for action we just mentioned? Well, based on the current legal landscape and timeline of active cases, the threat is probably not quite as immediate as the next few months. However, the lack of urgency with which the Oregon legislature seems to be handling this means they could be setting themselves up for a historic fumble.

The “Ticking Time Bomb” Lawsuits

So realistically-speaking, what could actually happen that would cause MountainGuard to leave—and consequently trigger a statewide resort shutdown? Well, the company did cite that a single major verdict could cause it to leave the state, and a few major cases making their way through the legal system could very well be the “nuclear verdict” that would force the company’s hand. Take, for example, the most high-profile active case: a $6.2 million lawsuit filed in early 2025 by a ski coach who was struck by a snowmobile at Mount Hood Meadows. While the case is likely months away from settlement or trial, it is significant—and could result in a large payout. In addition, the wrongful-death lawsuit against Mount Bachelor, which seeks nearly $50 million in damages, is still winding through the legal process after being filed in August 2022. There could be other non-public cases or other factors that could cause MountainGuard to leave in the coming months too; for example, the Mount Hood Skibowl case that forced the mountain to shut down its bike park wasn’t even reported on until the eight-figure verdict came down.

The Oregon Government’s Leisurely Timeline

So how should we look at these cases now? Well, for the state of Oregon, there’s some good news and some bad news. The good news is that while these cases remain a looming threat, they’re unlikely to reach a verdict or settlement before this fall’s insurance renewal period. Most Oregon ski resorts operate on annual insurance cycles that renew in September or October, so unless something unexpected like an accelerated settlement or surprise verdict happens, it’s likely that MountainGuard will remain in the Oregon market for at least one more winter.

But here’s the bad news: the threat hasn’t gone away, and the major lawsuits currently in motion could very well result in eight-figure payouts over the next 12 to 18 months, which could force MountainGuard to exit before the 2026-27 season. But perhaps the most concerning part of this whole situation is there’s very little chance the state will act in time to prevent that outcome. Oregon’s next legislative session won’t be until February 2026, which is already over six months from now at this point. But in even years, the state’s legislative session is just 35 days long, practically only allowing for priorities like budgets, transportation, housing, and public safety—and making it exceedingly unlikely that liability reform would even be considered for debate. It is worth caveating that in recent days, an emergency session was called for this upcoming August; however, it’s narrowly focused on transportation funding and transit layoffs, so the chances of liability insurance being taken up are essentially slim to none. So unless another emergency session is called or a surprise court ruling comes about, the legal environment is unlikely to improve before February 2027—and by that point, there’s a concerningly real chance it will be too late.

The Oregon legislature’s comically short session length in even years means that it won’t realistically be able to tackle the liability crisis again until 2027—unless it calls an emergency session.

Final Thoughts

The collapse of Oregon’s ski resort liability protections was set in motion by a tragic injury and what one could reasonably assume was a well-meaning court ruling. But a decade later, the lack of a legislative fix threatens the survival of the state’s entire ski industry.

Ultimately, the sky isn’t falling quite right now, and it’s more likely than not Oregon’s ski industry will have one more season of insurance left. However, if no action is taken soon, the window to avoid a full-scale coverage collapse in the coming months could close fast. For now, all eyes are on the legislature, the courts, and the lone insurer left.

So with all of this being said, is there any way you can take action? Well the biggest way is if you live in Oregon, contact your state legislators and tell them how you feel. If you don’t live in Oregon, consider supporting organizations like Protect Oregon Recreation, which are actively lobbying for legal reform in this space and could use all the help they can get. And finally, no matter where you live, tell your friends and family about this—the more people who put pressure on the key players here, the more likely lawmakers are to prioritize solutions before there isn’t a ski season anymore.

Adventures Trending

Conditions & Atmosphere Weather: Cloudy, with a high near 70. Light north wind. Vibes: There are a couple morning sprinkles out there, as we are right on the edge of a storm boundary passing to the south. Good news is that the North Country will stay primarily […]

ViewsConditions & Atmosphere

- Weather: Cloudy, with a high near 70. Light north wind.

- Vibes: There are a couple morning sprinkles out there, as we are right on the edge of a storm boundary passing to the south. Good news is that the North Country will stay primarily dry today and for the foreseeable future. On that topic, Vermont has endured 7 months straight with some precipitation over the weekends, but finally, it looks like that trend will end. Pair that with more comfortable temperatures and less humidity, and we can queue up whatever adventures our feet will lead us on.

Today’s Highlight

Vermont Country Fair!!! 5:00 pm – 8:00 pm. All ages. The Village Green.

There’s nothing like a summer night at Smuggs Vermont Country Fair. The Village Green comes alive with the smell of maple kettle corn and Waffle Cabin wafting in the air. Live tunes from Jammin’ Sam and the House Band set the vibe, and kids are dancing without a care in the world. Stroll the vendor booths, challenge your family to the wheelbarrow or water balloon toss, and let the little ones go wild, winning prizes at the midway-style games. The relay races and games bring out everyone’s playful side, and the energy from our activities crew is absolutely infectious. This is a Smuggs tradition, a memory in the making, and a must-do part of any summer vacation here.

This Weekend

Live music at Martell’s at the Red Fox:

Dead/Not Dead.

Saturday, August 2, 6:00 pm – 9:00 pm.

Great food and even better people. Check out this local restaurant and take in some music to soothe the soul at the same time.

Insider Tip

The next few days were made for adventure. With perfect Vermont summer weather on tap, the doors are wide open for swimming, paddling, biking, hiking, fishing, disc golfing, and all-out exploring. Whether you’re soaking in the sun at Bootleggers’, zipping through the treetops at ArborTrek, or chasing waterfalls on the trail, everything is in play. On-site or off, the Green Mountains and Smugglers’ Notch are yours to discover. Need help picking your path? The Ski & Ride desk has maps, tips, and guides ready to steer you to your next great memory. So, what are you standing there for, get up, get out, get out of the door.

Text Smuggs to 855-421-2279 for real-time alerts about weather updates, schedule changes, and more!

Text Smuggs to 855-421-2279 for real-time alerts about weather updates, schedule changes, and more!

The post Adventures Trending appeared first on Smugglers’ Notch Resort Vermont.

Newsweek

Best Disc Golf Courses 2. Brewster Ridge at Smugglers’ NotchJeffersonville, VT Nestled at the base of the highest peak in the Green Mountains you’ll find Brewster Ridge, an 18-hole disc golf course that’s so beloved it’s a favorite for PDGA championship events. You’ll especially enjoy […]

ViewsBest Disc Golf Courses

2. Brewster Ridge at Smugglers’ Notch

Jeffersonville, VT

Nestled at the base of the highest peak in the Green Mountains you’ll find Brewster Ridge, an 18-hole disc golf course that’s so beloved it’s a favorite for PDGA championship events. You’ll especially enjoy playing during Vermont’s famously beautiful autumn, sending your disc flying past the gold and crimson trees that line the course. Four tees on each hole help every player in your group find their perfect shot.

4. Fox Run Meadows at Smugglers’ Notch

Jeffersonville, VT

Once part of the Brewster Ridge disc golf course, Fox Run Meadows now stands on its own as an 18-hole course for the sport’s top tournaments. Bring your dog as you roam through the forests and hills of the Green Mountains, practicing your long-distance shots and short approaches along the way. Every hole has four tee boxes so you can pick the ideal spot to wind up and let your disc fly.

The post Newsweek appeared first on Smugglers’ Notch Resort Vermont.

Stretch and Go!

Conditions & Atmosphere Weather: Widespread haze before 8 am. Sunny, with a high near 81. Northwest wind 6 to 9 mph. Vibes: Summer weather at its finest at Smuggs today. There will be a little haze that will burn off, and then the sun will be shining, […]

ViewsConditions & Atmosphere

- Weather: Widespread haze before 8 am. Sunny, with a high near 81. Northwest wind 6 to 9 mph.

- Vibes: Summer weather at its finest at Smuggs today. There will be a little haze that will burn off, and then the sun will be shining, allowing you to really open up that playbook. Dial up a deep post route, take the long shot, and make today a touchdown.

Today’s Highlights

- Activities:

- Stretch & Go. 8:00 am, and 10:00 am. Ages 15 & older. Gazebo on the village green.

- Smuggs I-Did-A-Cart. 10:30 am, and 1:00 pm. All ages. Adventure Tent.

- Special Event: Smuggs Backyard Bash and BBQ. 5:00 pm. All ages. Village Green. Lawn Games, Music, Magic, Tie-Dye. Food and Drinks, S’mores kits.

Looking Ahead

- Jeffersonville Farmers’ Market. Wednesday, July 30, 4:00 pm – 7:00 pm.

The Farmers’ and Artisan Market unites our community’s producers, musicians, and neighbors with weekly live music. Enjoy the freshest local foods and more. You can find our summer market at 49 Old Main Street, in the field at the Route 15 & 108 South roundabout intersection. Please access parking at the silo space and the field off Old Main Street.

https://www.jeffersonvillefarmmarket.com

- Line Dancing. Wednesday, July 30, 6:00 pm – 9:00 pm.

Join Better In Boots at the Boyden Valley Barn every other Wednesday night from 6:00 pm – 9:00 pm starting June 18th, ALL SUMMER LONG! Come out for a fun, welcoming night of line dancing, great food, and local brews! Whether you’re brand new or have a few dances under your belt, there’s something for everyone. We’ll teach a new dance each week, most around 32 counts, though the speed and difficulty may vary. After the lesson, stick around for open dancing and song requests to close out the night.

- Schedule:

6:00 pm – Open dancing & warm-ups

6:15 pm – Lesson begins and continues through roughly 7:30 pm - Followed by open dancing & requests until 9:00 pm

- Beginner-Friendly!

No experience required—we’ll teach you everything you need to know! - A Few Quick FAQs:

Purchase tickets to reserve your spot or pay Cash at the door! Do I need boots? Nope! Wear whatever is comfortable. Is this couples dancing? No, this is single line dancing—though you’re welcome to turn it into a partner dance if you like. Hydration reminder: This is exercise! Please stay hydrated. The bar will be open for drinks and you can bring your own water! Clean shoes, please! If your shoes are muddy, bring a clean pair to change into for the dance floor. Do I need to know how to line dance? Absolutely not—that’s what I’m here for!

Can’t wait to see you there! Let’s dance!

https://www.smuggs.com/event/line-dancing/2025-07-30/

Text Smuggs to 855-421-2279 for real-time alerts about weather updates, schedule changes, and more!

Text Smuggs to 855-421-2279 for real-time alerts about weather updates, schedule changes, and more!

The post Stretch and Go! appeared first on Smugglers’ Notch Resort Vermont.

Friendly Friday

Conditions & Atmosphere Weather: Showers, with thunderstorms also possible after 2:00 pm. High near 77. Southwest wind around 7 mph, becoming northwest in the afternoon. The chance of precipitation is 80%. Vibes: It can’t always be sunny, right? After four straight beauties, today looks to be a […]

ViewsConditions & Atmosphere

- Weather: Showers, with thunderstorms also possible after 2:00 pm. High near 77. Southwest wind around 7 mph, becoming northwest in the afternoon. The chance of precipitation is 80%.

- Vibes: It can’t always be sunny, right? After four straight beauties, today looks to be a bit gray and wet. Don’t fret, the weekend is lining up to be lovely, so our jackets and umbrellas will only be a temporary necessity.

Today’s Highlights

- Activity:

- Llama Treks 10:30 am – 1:00 pm. All ages. Village Recreation Area.

- Disc Golf Challenge 8:00 pm – 9:00 pm. All ages. Village Green.

- Event: An evening with Rockin’ Ron the Friendly Pirate. First, it’s the family sing-along from 4:30 pm – 5:00 pm, then we have Bingo from 5:00 pm – 5:45 pm, and concluding with Capture the Flag from 6:00 pm – 7:00 pm. Everything takes place out on the Village Green. You might think Ron’s favorite letter is “R”, but it’s the “C.”

Looking Ahead

- Annual Jig in the Valley July 27, 12:00 noon – 8:00 pm.

Join us on the green in East Fairfield, rain or shine, for a day of great music, fabulous homemade food and desserts, kid’s activities, 50/50 raffles, a flea market, a silent auction, and so much more… Dale and Darcy, The Missisquoi River Band, Rusty Bucket, The Nobby Reed Project, The Oleo Romeo’s Big Variety Show, and Christine & The Beautiful People are among the musicians slated to perform. Ticket prices collected at the event entrance are $10 per person or $25 for a family! Bring your blanket, lawn chair, dancing shoes, and well-behaved dogs (on a leash, please) for the biggest annual event and fundraiser for The Fairfield Community Center, celebrating summer, our community, and life itself!

Text Smuggs to 855-421-2279 for real-time alerts about weather updates, schedule changes, and more!

Text Smuggs to 855-421-2279 for real-time alerts about weather updates, schedule changes, and more!

The post Friendly Friday appeared first on Smugglers’ Notch Resort Vermont.

Trail Talk: Mapping the Notch

While the lifts may be quiet and the trails green, things are far from sleepy up on the mountain. Our Mountain Ops team has been busy with the usual summer maintenance—tuning equipment, inspecting lift lines, and keeping everything in top shape behind the scenes. But […]

ViewsWhile the lifts may be quiet and the trails green, things are far from sleepy up on the mountain. Our Mountain Ops team has been busy with the usual summer maintenance—tuning equipment, inspecting lift lines, and keeping everything in top shape behind the scenes. But there’s one big project we’re especially excited about this season: our ongoing work with the Snowright System.

This summer, we’ve spent a ton of time trail mapping—creating a detailed digital baseline of the mountain’s natural terrain. Why does that matter? Well, it helps us know exactly how much snow we need to make to fill every dip, knoll, and corner on each trail, instead of relying on estimates. Not only will this lead to better coverage and longer-lasting snow, but it also means we can be smarter and more efficient with both water and energy—big wins all around.

The Snowright System will integrate with our snowmaking software to monitor the amount of water pumped on the hill, and it pairs with the technology in our groomers to measure snow depth in real-time. In short, it’s a precision snowmaking tool that’s going to help us make just the right amount of snow, right where it’s needed.

Oh—and speaking of grooming, we’ve got a brand-new snowcat arriving this fall, just in time to roll into the season with fresh treads and an even smoother ride.

We’ll keep you posted as more improvements roll out, but for now, just know your favorite trails are getting a little smarter this summer. Got questions about the snowmaking system or other behind-the-scenes updates? Let us know in the comments!

And while you’re waiting for flakes to fly, a quick shoutout to our longtime mountain messenger: Hugh Johnson recently received the NASJA Bob Gillen Award for his contributions to snowsports journalism—well deserved! He’ll be back sharing updates and snow stoke in just a few short months.

Stay cool, and keep dreaming of first tracks!

The post Trail Talk: Mapping the Notch appeared first on Smugglers’ Notch Resort Vermont.

Everything’s Right

Conditions & Atmosphere Weather: Sunny, with a high near 78. Calm wind becoming southwest around 5 mph in the afternoon. Vibes: Focus on today and you’ll find a way, happiness is how, rooted in the now, ’cause everything’s right. Today’s weather is the pearl of the week, […]

ViewsConditions & Atmosphere

- Weather: Sunny, with a high near 78. Calm wind becoming southwest around 5 mph in the afternoon.

- Vibes: Focus on today and you’ll find a way, happiness is how, rooted in the now, ’cause everything’s right. Today’s weather is the pearl of the week, not too hot, not too cold, and encased right in the middle. So, embrace your inner oyster and break out of your shell to make today a gem.

Today’s Highlights

- Activities:

- Rail Trail Bike Rentals 10:30 am – 3:00 pm. Ages 10 & older. Off-site.

- The Big Smuggle 9:00 am, 10:30 am, 12:30 pm, 2:00 pm. Ages 5 & older. Village Green.

- Events:

- Liquid Courage Adult Karaoke 9:00 pm – 11:00 pm. Ages 21 & older. Bootleggers’ Lounge.

- Jeffersonville Farmers’ Market 4:00 pm – 7:00 pm. 49 Old Main Street, Jeffersonville.

Looking Ahead

- Tomorrow’s weather looks to be sunny, humid, and hot. Lots of fun water adventures to be found in and around the Resort. For the folks out there still looking to get active, check out the Peak and Pond Hike, led by one of our longest tenured guides, Martha. Trek into the deep woods of Vermont, the tree top canopy acting as your sunshade, and explore an old-growth forest with unique rock formations deposited ages ago by glaciers. Finish your adventure with a refreshing swim, the perfect ending on a hot day.

- Looking to get a workout in while on vacation. Check out the Aqua Strong fitness class, for ages 16 & older, every Tuesday and Thursday, starting at 9:15 am at the Mountainside Water Playground. Led by fully certified Laura Thomason, it’s a great way to play without skipping leg day.

- Another option tomorrow for exercise plus water is the Stand-Up Paddleboard Yoga. Local yoga instructor Mindy creates a welcoming space where you can perfect your poses paired with practicing your paddling skills. Major points if you can balance on water in the Vrikshasana (tree pose) if it were me, I’d probably excel at the Shavasana (corpse pose.) The class starts at 10:00 am at Bootleggers’ Basin, for ages 13 & older.

Text Smuggs to 855-421-2279 for real-time alerts about weather updates, schedule changes, and more!

Text Smuggs to 855-421-2279 for real-time alerts about weather updates, schedule changes, and more!

The post Everything’s Right appeared first on Smugglers’ Notch Resort Vermont.

Mountain Collective Adds Whiteface, New York for 2025-26 Season

Whiteface becomes the third U.S. Northeast resort to join the Collective, which has retained a western-heavy portfolio in recent years but has made serious strides towards rectifying that. New York’s Whiteface will join the Mountain Collective Pass for the upcoming 2025-26 season, according […]

Mountain

Whiteface becomes the third U.S. Northeast resort to join the Collective, which has retained a western-heavy portfolio in recent years but has made serious strides towards rectifying that.

New York’s Whiteface will join the Mountain Collective Pass for the upcoming 2025-26 season, according to New York State’s ORDA. At 288 acres with a 3,430-foot top-to-bottom footprint, Whiteface is home to the longest vertical drop in the Northeast. Collective Pass holders will get two days of unrestricted access at Whiteface next winter, as well as all other mountains on the pass.

Whiteface becomes the fifth Northeast ski resort on the Collective for 2025-26, joining Maine’s Sugarloaf and Sunday River and Quebec’s Bromont and Le Massif de Charlevoix. For the upcoming winter, Mountain Collective will now offer two-day access to 27 destinations around the globe, 20 of which are in North America (Arapahoe Basin has left the pass for 2025-26).

Notably, Whiteface becomes the first-ever Mountain Collective partner in New York. This also marks the first time Whiteface has joined a multi-mountain pass (besides ORDA’s Ski3 pass) since the dissolution of the MAX pass in 2018.

Our Take

The Mountain Collective Pass has struggled to establish a strong presence in the Northeast, especially after losing Sugarbush a few years ago. Until recently, the pass included only two Northeast mountains—Le Massif and Sugarloaf—leaving it with no representation in Vermont and offering limited appeal for skiers and riders based in New York or the surrounding areas. While last year’s additions of Sunday River and Bromont helped a little bit, the pass’s primary competitors—Epic, Ikon, and Indy—each maintain a far more robust presence in the region.

Adding Whiteface aims to help change that. Though the mountain isn’t perfect—it’s known for its wind-exposed layout and occasional resiliency issues—the move restores a competitive destination to the East Coast within reasonable driving distance of New York City. It probably still isn’t enough to make the pass a viable alternative to Epic or Ikon’s base options in the Northeast, but Mountain Collective is now a bit more versatile for East Coast skiers, especially those within reach of the Adirondacks.

Considering the Mountain Collective Pass? Check out our detailed comparison against competing Epic, Ikon, and Indy offerings. You can also check this comparison out in video form below.

The Monday Message

Conditions & Atmosphere Weather: Mostly sunny, with a high near 65. Northwest wind 8 to 10 mph. Vibes: The air is crisp out there this morning, like a fresh apple in the fall. It’s a great day to get active, and like Mondays in the real world, […]

ViewsConditions & Atmosphere

- Weather: Mostly sunny, with a high near 65. Northwest wind 8 to 10 mph.

- Vibes: The air is crisp out there this morning, like a fresh apple in the fall. It’s a great day to get active, and like Mondays in the real world, a chance to plan out what your week might look like. The weatherman’s telling us it ain’t going to rain till later in the week, so you shouldn’t be sitting in your drop-top soaking wet. Nor will you be in a silk suit trying not to sweat. So, make this the year that you won’t forget. Temperatures will steadily increase throughout the week, so take that into account while making your weekly itinerary.

Today’s Highlight

- Activities:

- Stretch & Go 10:00 am – 11:30 am. Ages 15 & older. Gazebo on the Village Green.

- Summer E-Bike Adventure Tour 11:00 am – 3:00 pm. Ages 12 & older. Off-site. Lamoille Valley Bike Tours.

- Event: Comedy Night for Adults 9:00 pm – 11:00 pm. Ages 21 & older. Lower level of the Meeting House.

Insider Tips

- Start your morning with a coffee and a morning pastry from The Perk. Then pick up all your necessities for a day outdoors from The Country Store while you’re there. Fueling and stocking up before you go equals more time enjoying what your day may bring.

- Do you have kids 10-15 years-old? The High Adventure Specialty Program is a full day of exhilarating challenge with activities like rock climbing, kayaking, and a session at ArborTrek. Sign-up today, as these camps will fill-up fast.

- Take a good look through the Weekly Activity Guide and check out the Hours of Operation to ensure where to be and when to be there for all your favorite activities, shopping, and dinning. Have a great week here at Smugglers’ Notch Resort!

Text Smuggs to 855-421-2279 for real-time alerts about weather updates, schedule changes, and more!

Text Smuggs to 855-421-2279 for real-time alerts about weather updates, schedule changes, and more!

The post The Monday Message appeared first on Smugglers’ Notch Resort Vermont.